Telling queer stories transmits our history, providing the opportunity to learn about our experiences and inspire the next generation. Storyteller Jeffrey Canton gives us some tips on how to document our stories, and tells us why they’re important to share…

By Stephan Petar

If you open QueeringTheMap.com, a website by Luca LaRochelle, you’ll find anonymous notes from people sharing what certain locations worldwide mean to their queer experience. These micro-stories are about dressing in drag, first kisses, dancing, heartbreaks, memorable dates and more.

The map illustrates that queer stories – particularly relatable ones about daily life – are everywhere. Yet we hardly hear them, and if we do, they’re shared among close friends or anonymously documented on websites like Queering the Map.

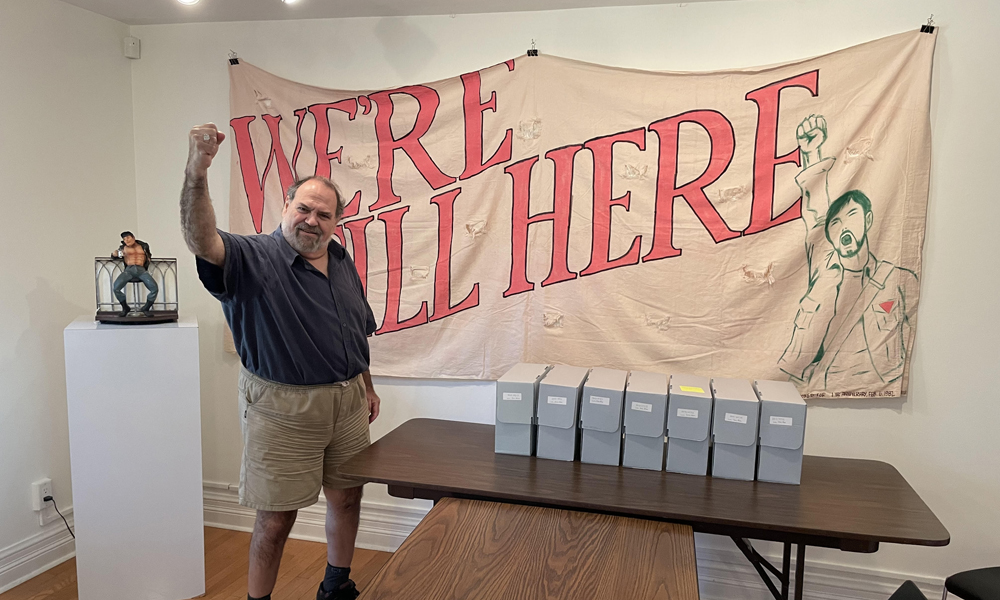

We all have stories that can contribute to the 2SLGBTQI+ narrative. Documenting our history, big or small, is something storyteller Jeffrey Canton urges us to do. Canton hosted a Storytelling Toronto workshop with The ArQuives, Canada’s largest independent 2SLGBTQ+ archives, called Keeping our Stories Alive: Processing LGBTQ2S+ Histories, that explored the importance of preserving personal stories as a way to contribute to queer history.

Canton, a former teacher and children’s book reviewer, has been a storyteller for more than three decades. He is a member of Queers in Your Ears, Toronto’s oldest 2SLGBTQI+ storytelling collective, and hosts the online course Transformations with Storytelling Toronto (which returns in January). I spoke with him to better understand why 2SLGBTQI+ individuals may be hesitant to share their stories, how to document them, and why they should.

The challenges of telling a story

Speaking to people in the community, I discovered that some keep their stories private because of a fear of repercussions or because they think it’s too personal or embarrassing. Others noted that they feel their stories are not significant enough – to which Canton responds, “I think a lot of queer people think they have to talk about being a part of something big for their story to be worth telling.… That for me is an enormous mistake.… It’s the small stories that are a way of transmitting our history as queer people.”

Stories of the Bathhouse Raids, HIV/AIDS and queer protests are all extremely important, but Canton notes that smaller tales are also impactful. Stories of first loves, public hand holding and cruising, among others, are also important historical records, but he believes we don’t tell them because many “don’t think ordinary people’s experiences are important.”

Canton recalls his first time going to St. Charles Tavern…almost. “I went down to the St. Charles when I was about 18 and walked up and down Yonge Street, terrified to go in because I had never been to a gay bar. I never managed to get in.… I was too afraid.” While that story may seem typical of many first gay bar encounters, that’s okay. It’s a universal and relatable story that’s important to understanding our overall experience as a community.

He also acknowledges some stories may be difficult to tell. “Sometimes you’re not ready to tell a story.… Sometimes they’re too hard to tell at a particular moment, and waiting is okay.”

How to document your story

Another challenge is the storytelling aspect. “Telling a story isn’t as easy as many think.… A good story has to be well crafted, have a trajectory and draw an audience,” he explains.

“Ask why you want to tell this story,” he says. Ask yourself, “What does it tell others about you as a member of the queer community?” Also, don’t be afraid to get personal, if you’re ready, he advises, encouraging people to think of transformative moments in their life. He recommends getting the story on paper, even if it is bare bones, and to really consider the who, what, where, when and why.

Details are important, and as memories fade, we may need to turn to outside resources to piece everything together. “Start by finding things where you are. What does the landscape look like?” This could be revisiting the backdrop of your story and observing it. However, as cities evolve, that memory you’re searching for could be lost to time. Luckily, local archives or Google Maps Street View can take you back. Canton also mentions Facebook groups like Vintage Toronto or those of defunct establishments, as group members may recall details like decor and atmosphere for you. “It’s the little details you add to your story that make it come to life.”

He also suggests talking to others who were there. “Memory is flawed. One way to challenge yourself is to have other people – friends or family – talk about it.” This gives another point of view, a perspective into parts you may have forgotten and how you made others feel.

After documenting your piece, consider sharing it. Canton encourages visiting the Storytellers of Canada website to find in-person and virtual events. However, if you’re like me, then publishing online or finding other artistic forms of expression can work as well.

Why do we need to document our stories?

All queer stories have historical value. “Our world changes, and because we have not been documenting our stories, there are huge gaps,” Canton notes. “It’s hard to find evidence of the 2SLGBTQI+ presence prior to the 1960s in a meaningful way.” Instead, he points out all the anti-queer material from mainstream media.

Not to mention, a majority of 2SLGBTQI+ stories are of white, gay men, as those from diverse groups or other parts of the 2SLGBTQI+ spectrum were overlooked. “People who are from the BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, People of Colour] community, we need to hear their story. We need to hear from queers with disabilities…as well as trans experiences.”

Lastly, stories provide the opportunity to compare. By having stories throughout time, we have a chance to see the evolution of queer life. For example, Canton wonders how a story about hand holding from 30 years ago would relate to one that is set today.

2SLGBTQI+ history is a living document that is always being added to. Our stories have been hidden for too long and lost with time. Yet, they can inspire, provide a sense of belonging, help people through confusing moments and allow those beyond our community to have a greater understanding of who we are. “Storytelling is a perfect way to keep those experiences and learn from them,” Canton ends.

So, get out your laptop, sharpen that pencil or fire up your ring light and open TikTok. We all have tales to tell.

STEPHAN PETAR is a born and raised Torontonian, known for developing lifestyle, entertainment, travel, historical and 2SLGBTQ+ content. He enjoys wandering the streets of any destination he visits, where he’s guaranteed to discover something new or meet someone who will inspire his next story.

POST A COMMENT