DJ Junior Vasquez opens up on surviving, slaying and synthesizing five decades on the dance floor…

By Elio Iannacci

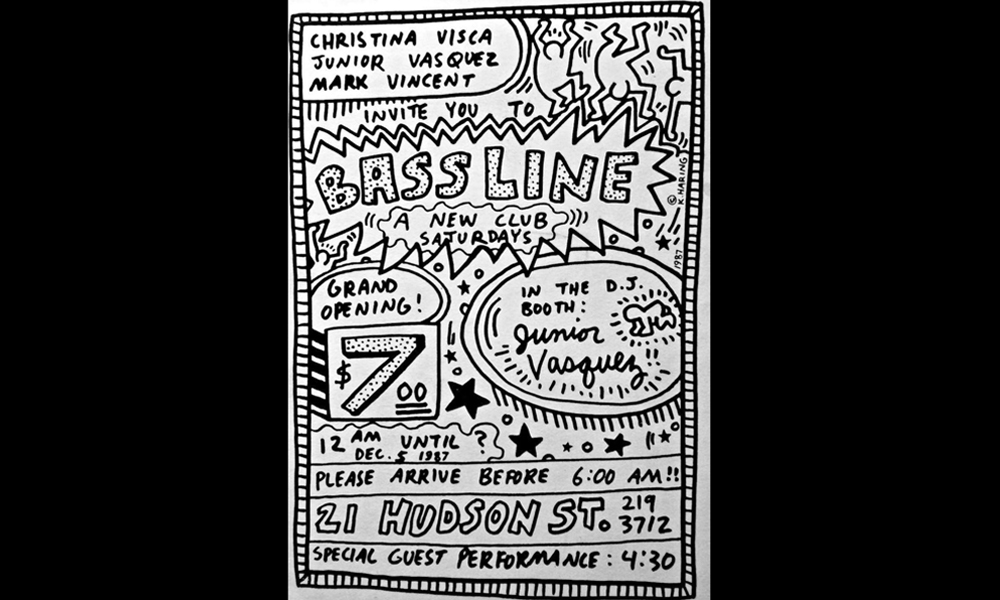

The trajectory of Junior Vasquez’s career is worthy of a Ryan Murphy-produced mini-series. Vasquez became one of the only gay DJs of his time to grab international attention, building from his early days in small, underground clubs like Bassline right through to his thousand-plus-crowds at Palladium and ArenA.

It all started when Vasquez – then Donald Mattern, his birth name – moved to Manhattan on Halloween night in 1971. He was looking for more than just a clever costume and a good party – he was hunting for a completely new identity. The Pennsylvania native realized he needed to get out of the hetero-centric environment he had grown up in and find the fuel he needed to thrive.

While living in the Big Apple, he discovered that he wasn’t able to find his new self while chasing an old dream of becoming a clothing designer – something he began to work towards while attending the Fashion Institute of Technology. Where he did find comfort was at the Paradise Garage and The Loft, two gay music meccas, where liberatory vibes helped clarify Mattern’s purpose. Tired of cutting hair and sweeping floors to pay for his tuition, he had a career epiphany while flipping through rows of vinyl at a record store on 42nd street. It was there, in the thick of the stacks of disco, R&B and soul music, that Mattern decided to drop out of school, change his name to Junior Vasquez and make his way into the world of DJing.

The rest is history.

Before becoming a household name on the decks and in the studio, Vasquez aided legendary producer Shep Pettibone on tracks in the mid to late ’80s (sessions ranging from Madonna’s “Causing a Commotion” and “Vogue” to Whitney Houston’s “So Emotional”) until he was eventually asked to remix major diva singles for his main fanbase: LGBTQ2IA+ clubgoers.

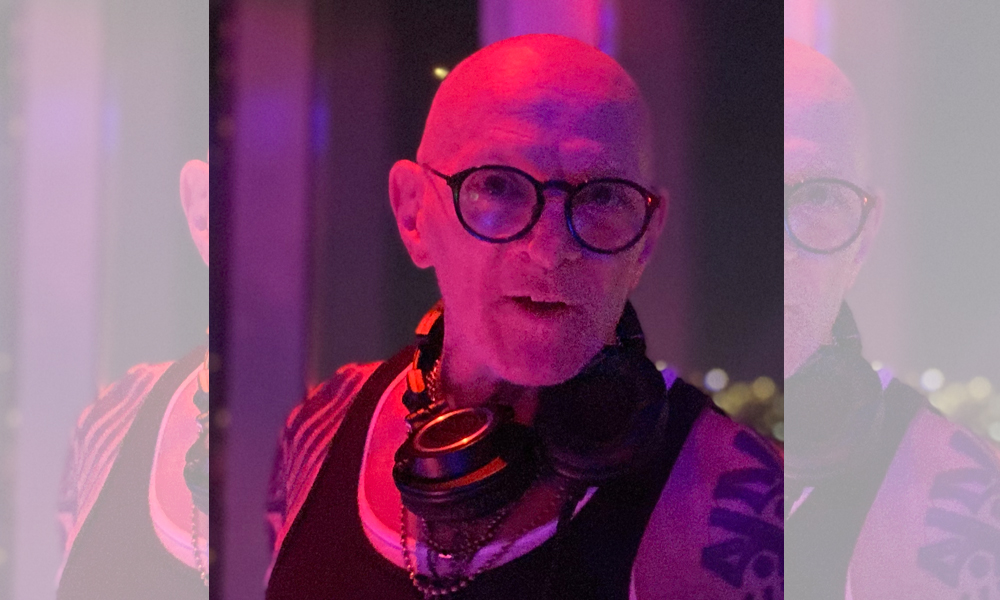

Vasquez noticed the shift in tastes happening under the mirror ball, with a growing gay community gaining access, visibility and power in a world that largely ignored, dismissed and oppressed them. His signature in the mid ’90s was blending classic house and disco into the aggressive, chant-heavy, drum-laden, build-up loaded genre dubbed Tribal House. His epic 14- to 16-hour club sets – inspired by the great gay DJs coming from African-American maestros such as The Paradise Garage’s Larry Levan and The Warehouse’s Frankie Knuckles as well as Italian-American groundbreakers like The Loft’s David Mancuso and Studio 54’s Nicky Siano – got Vasquez resident DJ gigs at the Sound Factory, Tunnel and ArenA in New York City (where his booth was famously designed by Dolce & Gabbana).

Vasquez’s rise represents a pivotal moment in queer music history that showcases a growing force in the community. His mixes – which swabbed the vernacular, attitude and culture off gay dance floors – were able to broadcast all the LGBTQ2IA+ messages he heard under the mirror ball and amplify them via his compositions.

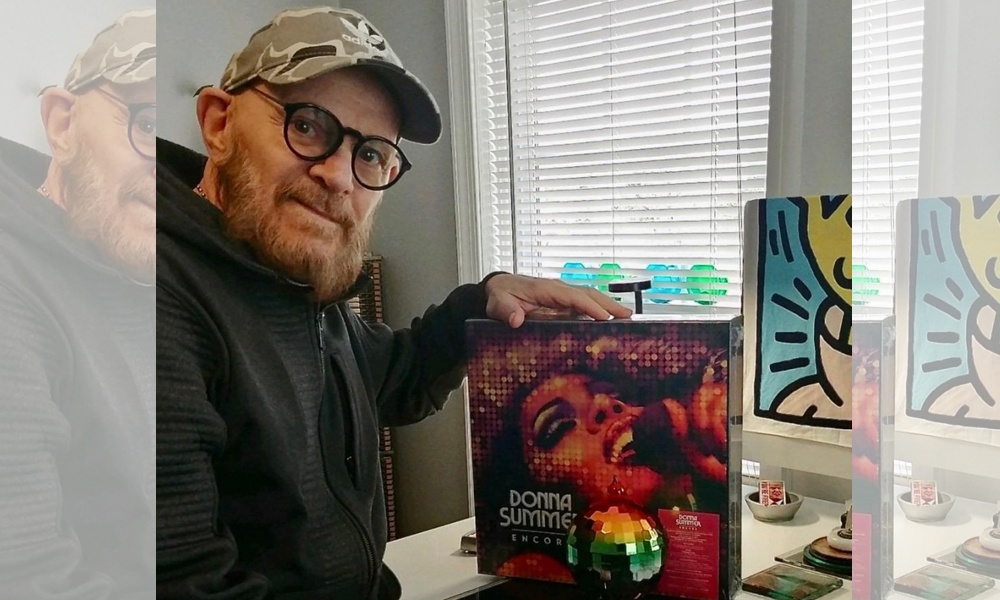

In the mid 2000s, Vasquez’s career was taken hostage by a dangerous addiction to crystal methamphetamine, which had him take a step away from the DJ booth for a number of years. Yet at the age of 73, whispers that Vasquez would be making an official return to New York City have not stopped. With his latest remix of Donna Summer’s “I’m A Rainbow” (for Summer’s posthumous I’m a Rainbow: Recovered & Recoloured), and the recent mass recognition of house music – ignited by Beyoncé’s Renaissance and Vasquez’s remixes on Madonna’s 2022 release, Finally Enough Love: 50 Number Ones – the DJ is primed for a comeback. Over the phone from his home in Pennsylvania, Vasquez reminisced with us on working his icons to make iconic work.

There are so many conflicting stories about why you changed your name. Your parents are of Italian and German descent, so what’s the deal?

I liked the name, because I hung out on 14th Street a lot where it was very Hispanic and very Latin and all the ladies were screaming and calling their kids, ‘Junior, come back to the house.’ That stuck on me because it represented this new period in my life. I ran away to New York because I didn’t fit in so I wanted to reinvent myself.

You were a fashion design student and suddenly dropped out of school. What did music give you that fashion couldn’t?

They both went together for me. I played a lot of music when I was drawing clothes – a lot of Barry White and The Supremes. I was a big Diana Ross fan, and I got so many ideas by listening to the way she hit the high notes.

You soon met Shep Pettibone and pretty much forgot about fashion. What did he have to offer you?

Oh yes. He was a big influence on me. He would pick his students to work with so they could learn how to edit music, and I was lucky to be one of them. I watched him really closely, but never asked questions. I never do. Soon, I found myself spending hours in the studio with him – sometimes three days in a row – eating Chinese food every night, and listening and hearing him test out the sounds, the hi hat, and hearing him repeat the music and listen for what he thought should be pulled out or exaggerated.

How did hearing David Mancuso and Nicky Siano change your sets?

I went to The Loft and The Gallery and saw them both play for their crowds and how they got the dance floor to react to what they were giving them. I got hooked. I learned from standing right beside their speakers and making notes in my head about how and why they’d put on certain songs to make a mood or tell a story. It felt like the same way I learned from my parents – just watching and absorbing. My dad was a drummer and my mom was an artist.

I got things from being at The Loft and The Gallery, but I didn’t copy. I’m not a replicator. I make every sound my own. I’d stand beside the speakers with Larry Levan at the Paradise Garage too, and when I went to bath houses early on to listen to Bette Midler – her voice and her performance and the echo of it off the walls – I remember hearing that blend together.

What was the biggest change you saw and heard when you moved from spinning at small clubs like Bassline to the Sound Factory?

First of all, the number of people. Baseline got very packed – it was a sweat box. Most people at other clubs would play really disco-y stuff, but I started seeing fashion changing and I began mixing everything so it would sound more of-the-times. I didn’t care if I made mistakes while I was mixing because I was human. But I noticed that the sound started getting harder.

After the Paradise Garage closed, everyone needed somewhere to go to and it felt like a new era. So many people used to say, ‘Where’s this white kid coming from playing all this serious music?’ I also started to design the club backdrops and picked the dancers on several nights so I was ready for the change. When I went over to Sound Factory, it was all about Chicago house music, deep house. Lots of bass, percussion, hand claps and big vocals. When I wanted to get moody, I didn’t need a lot of tracks – and the crowd picked up on that and liked it. On Friday nights I’d play there for kids that would come up after dancing at the Tunnel all night. There was break dancing and all that early hip hop, and I just blended it.

What changes did you see in the crowd?

I saw the confidence in the gay community growing. I felt it too when I played, because I allowed myself to be more creative and then I saw how the music sparked it in a lot of people and helped them to come out their shells. I felt like I gave them a home to go to. So many were thrown out of their house for being gay or queer or not what their family wanted them to be. It was interesting to see how the clubs would energize them to keep going no matter what was out there.

A few icons came along and asking you to remix their songs. A big Billboard #1 dance hit for you was Annie Lennox’s ‘No More I Love You’s’ Sound Factory remix. How did you think to reshape a song like that – in its changing slower tempos – that seemed almost impossible to remix?

I liked challenges and I was hooked on her Eurythmics look and persona and sound during her whole Sweet Dreams (are made of this) [era]. That time for her was fierce because it sounded like [Eurythmics] combined male and female vocals together and she did these amazing gestures with her voice that, to me, sounded really powerful. I wanted to bring back the image I had of her that was so fierce – her with that orange hair and her suit on and the ballsy androgyny – I wanted that in my ‘No More I Love You’s’ remix. So I pieced together a medley with the songs off her album Medusa [‘No More I Love You’s’, ‘Take Me To The River’ and ‘Downtown Lights’] so we could get back to the way she manipulated her voice on the ‘Sweet Dreams’ song. I recreated this complexity with her voice with filters so you hear the cross between hyper masculine and hyper feminine. With her album Medusa, I knew she really needed an edge.

At that time, many women over 30 – like Annie Lennox, Whitney Houston and Madonna – were thrown into this adult contemporary pool by record labels. Did you feel you were fighting against that with your remixes?

Oh yeah. I didn’t see any of them as adult contemporary. For Annie Lennox, I was looking for base lines from other songs of hers than the original song they gave me to do – which was just to remix ‘No More I Love You’s’ – so I stole from [‘Take Me To The River’] and [‘Downtown Lights’] to take [the remix] to another level of drama. I used whippet drum sounds and snare fills because I wanted that bigger sound – she needed to sound strong and sensual and kind of radical like ‘Sweet Dreams’ was, not dreary or soft, which was the sound that was happening to a lot of singers in the ’90s. So many!

I noticed a lot of them started getting produced to sound quiet and dreary – even though they had complex voices. I turned the volume up and focused on their powerful sides. I did it like this because I was always experimenting with what sounded the best out of the speakers on the dance floor so it was like I was giving them a boost. A club version of a song needs to be bigger than the single – it needs to hit harder and sometimes be more than the original. That’s why I had these long remixes where I can stretch notes or the chorus or add filters or sounds.

Remixes weren’t given a lot of respect by record companies at the time, even if DJs were commissioned to mix them. Many DJs I’ve talked to said record companies in the 1990s thought remixes were too gay-sounding or too Black-sounding for a wide release. Did you encounter that kind of homophobia as well?

I went through that a lot of times because I wasn’t really accepted. So many of these songs or remixes – I don’t know where they are or who has them. It took a lot for me to make friends in the business, like Anthony Pinto and Clive Davis. Others would criticize my work or say it was too gay. The problem was always that these companies would give you the track and say, ‘Do whatever you want’ and then you would do your thing and your version would disappear because they’d want something else…even though I ended up having a lot of number ones on Billboard dance charts.

Some of your earlier songs – both as Junior Vasquez and as your pseudonym, Ellis D – are defined as ‘Bitch Tracks.’ I want to talk about what that means to you and how you created them.

I used to go to the [vogue] houses in the Bronx and sit there and watch the Ballroom happen and listen to the music. There’s a certain tempo that made its way into my music. It’s like stabbing with the sound because you’re essentially stabbing your opponent with a vogue pose or gesture or whatever. I’d go to the Piers in my jeep and play music and hear the conversations and that made it into the music. We had a runway in a few of my clubs [which would divide the dance floor] – a lot of the house kids and drag queens waited the whole night to hear the bitch tracks and perform them with a spotlight on them. The big [Bitch Track] for me was ‘Work This Pussy’ and then ‘Get Your Hands Off My Man’ – I would make these songs for this particular runway crowd.

Madonna would look for dancers to work with her at the Sound Factory. Aside from obviously playing for partyers, did you want that environment to be a space for a lot of that queer art to get recognized?

Of course. I would do it with the sound too and mess with whoever was dancing in the spotlight. It was a different concept for me then, but I kept going at it. I liked to torture the dancers…not in a bad way, but to really challenge them with strange beats and stuff, mixing in looney tunes or lines from movies or switch around beats, the tempo, the keyboards, and slow them down or speed them up. They would learn how to react. It was a collage of sounds and interruptions [and it] made everyone on the dance floor pile around these voguers and drag queens and watch them carry on. It was art.

You worked on Madonna’s ‘Vogue’ before going on to remix ‘Secret’ and ‘Bedtime Stories.’ People are revisiting all three songs now because of the new Madonna album. What do you remember about your contribution?

It all happened because Shep [Pettibone] had worked with Madonna a long time – before that we did ‘Vogue.’ I’d like to say it came out of the Sound Factory because she would come down there. I would start playing sometimes at 10 pm, and she’d come into the booth. At that time it wasn’t crowded yet, so you could see the dance floor and she saw [dancers] Jose Gutierez and Luis Xtravaganza. They were the stars of that Sound Factory runway show. They were a big deal and she saw that they stole the show – they were primo.

We were like brother and sister for a while, but a real triumph for me was mixing ‘Bedtime Stories’ and ‘Secret’ were definitely a turning point.

How so?

Those remixes were very emotional for me. To make them took a spiritual tone because you can hear the gospel sound that I was drawing from. I was focused and wanted no distractions when I did them.… I really listened to what my heart, my soul and my brain were telling me with those ones. I had a lot of things happen in my life and that brings me back. When someone like Madonna or Whitney is singing, I hear it a different way and that’s why I change it. A lot of conservative people would knock the way I see it and mix as being too gay or too queer, but it got to a point where I would say ‘fuck it – I like the way it is’ and stand up for my work. It was like standing up for my vision.

How do you see the New York club scene today?

A lot of it changed dramatically because they’re back to the old strip joints and then bottle nights and champagne and lap dances. That’s going to change. It always does.

You were on Andy Cohen’s Watch What Happens Live recently and said that you were making an album with Whitney Houston at some point. Do you still have the demos?

Yes. There are a lot of songs. I went out a Jersey and worked with her in her house. She’d buzz me and the guys working on the album through the intercom when I was in the studio and ask if we wanted breakfast, and she’d bring it down in her robe and fuzzy slippers. She was so cool. She did the right thing by me as far as when all her double album came out and put my remixes on it.

You’ve just become a voting member of the Grammys. Do you feel you have a fighting chance of getting appreciated by the Academy this year?

Well, they haven’t recognized me yet but I’m still on a mission to win a Grammy. I’m still waiting to get recognized and get a statue. I’m hoping my ‘I’m A Rainbow’ remix by Donna Summer will finally get me one, but we’ll see. I’m hoping they’re not going to overlook me now.

You’re currently working on new music. What are you most interested in exploring next?

More a throwback to my Bassline days – back to my roots with Chicago House. I like the idea of adding my electronic spin to it… and making another anthem or two.

ELIO IANNACCI is an award-winning arts reporter and graduate student at York University whose research interests include ethnomusicology and gender studies. He has contributed to more than 80 publications worldwide, profiling icons such as Barbra Streisand, Lady Gaga, Aretha Franklin and Beyoncé. His academic work is supported in part by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

POST A COMMENT