The story of two affluent gay teens who set out to commit the “perfect crime”—and fail miserably…

If you’re a true crime fan, you know there’s no shortage of books, documentaries, podcasts and original reporting dedicated to the victims of violent crimes and the people who commit those crimes. At the same time, we know the cases that get the most attention are usually ones that are committed against white, middle class, cisgender people. Meanwhile hate crimes, including murders of gay, trans and non-binary people are on the rise. Queer Crime is a monthly column focusing on true crime with an LGBTQ+ spin whether it’s the victim or the perpetrator.

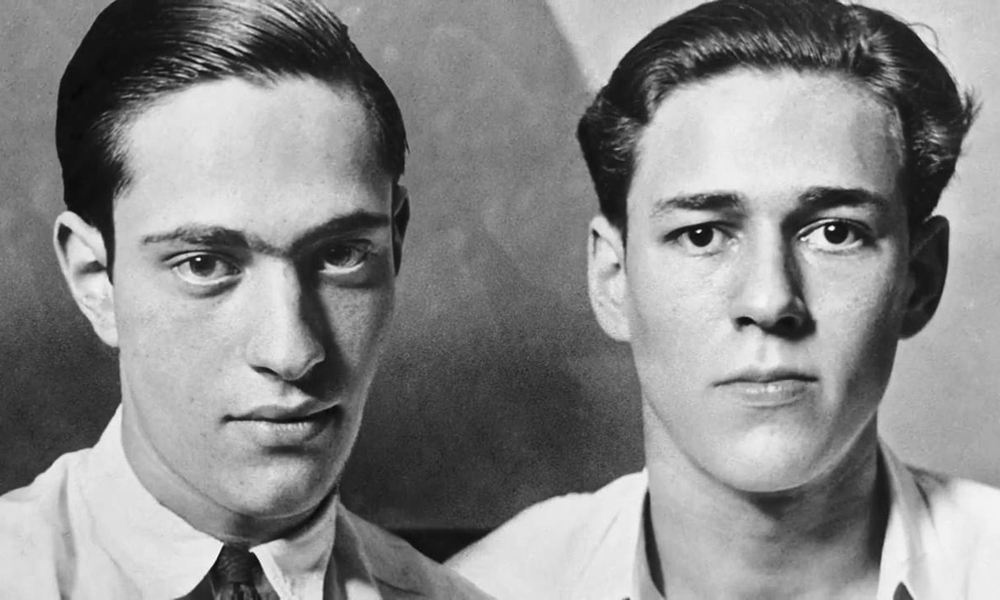

This month, we’re going back to the year 1924 and revisiting “the crime of the century”, the murder of 14-year-old Bobby Franks by Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb. The two teens (19 and 18 respectively) set out to commit what they thought was “the perfect crime” but did almost the exact opposite and were arrested within days of the murder. While some reports of the case hint at the partnership between Leopold and Loeb being romantic, the true details of their relationship have been up for interpretation.

Leopold and Loeb, who were both wealthy college students from Chicago, spent seven months meticulously planning the murder of Bobby Franks. From mapping out the abduction and ransom demand to choosing the method of murder and how to hide the body, the two men were interested in committing murder not because they enjoyed violence but because they believed getting away with it would prove their intellectual superiority.

On May 21, 1924, Leopold and Loeb murdered Franks by stabbing him multiple times with a chisel. There is debate over whether it was Leopold or Loeb who physically committed the murder, but the general consensus is that Loeb was the dominant of the pair and Leopold’s obsession with Loeb led him to follow along. In his autobiography Life Plus 99 Years, Nathan Leopold wrote ”Loeb’s friendship was necessary to me—terribly necessary” and that his motive, “to the extent that I had one, was to please Dick.”

Although they meticulously planned the crime and didn’t expect to get caught, they made a number of mistakes that led the police straight to them. Along with alibis that were easily proven false, a pair of prescription eyeglasses were found near the body—and they turned out to be Leopold’s. During questioning, Leopold and Loeb turned on each other and confessed separately, both claiming the other was the one who committed the actual murder.

The pair plead guilty to avoid the death penalty, but the sentencing hearing that followed lasted a month. One piece of evidence presented by the prosecution was a letter written by Leopold claiming that he and Loeb were having a homosexual affair. The prosecution tried to present their relationship as a contributing motive, calling them “cowardly perverts”. Their lawyer, Clarence Darrow, countered by claiming his clients’ homosexuality proved they were insane and they should not be put to death for their actions.

They were spared the death penalty and sentenced to life in prison instead. Loeb was killed in prison by another inmate who claimed Loeb was making “sexual advances” towards him, and Leopold was released in 1958 after serving 33 years.

There are a number of fictional works based on the case. Compulsion (book 1956, film 1959) touches on Leopold’s obsession with Loeb. The 1992 film Swoon explores the ways the dominant Loeb was able to control the more submissive Leopold by using sex as a weapon. The 2002 film Murder by Numbers pulls back on the explicit homosexuality but emphasizes the power dynamics—and power struggles—between the two leads.

Alfred Hitchcock’s 1948 film Rope, which is also based on the Leopold and Loeb case, is universally considered to be one of his “gay films” along with Strangers on a Train. Since the Hays Code made it impossible to show homosexuality on film, Hitchcock uses “gay coding” instead to portray that the two main characters are not only friends, but lovers. The screenwriter Arthur Laurents has also said Rope “is clearly about homosexuals. The word is never mentioned, not by Hitch, not by Warner’s, where it was filmed. It was referred to as ‘it’. They were going to do a picture about ‘it’, and the actors were ‘it’.”

While some 1940s audiences wouldn’t notice the references to homosexuality in Rope, the gay coding is clear as day now. From the physical closeness and distinct post-coital behaviour of the two main characters after they commit murder to parallels between the body in the trunk and being “in the closet”, the references are hard to miss if you’re paying attention.

There have also been a number of stage plays based on the case such as Thrill Me: The Leopold & Loeb Story (2003), Never the Sinner: The Leopold and Loeb Story (1988) and Rope (1929), which was then adapted to film by Hitchcock. In his book Murder Most Queer, theatre scholar Jordan Schildcrout examines how the trope of the “villainous homosexual” has evolved over the years and how the fictionalized versions of the Leopold and Loeb case fit in.

Even though the Leopold and Loeb case is almost a century old, it’s no wonder it continues to inspire new adaptations. It has everything: charismatic main characters with something to prove, a forbidden love affair, a shocking murder, courtroom drama, untimely deaths and a redemption arc. In 1924, their homosexuality was positioned as an explanation for why Leopold and Loeb killed. Today, since versions of the “gay panic defence” are permitted in some states, it’s still possible to use the expression of sexuality as a way to justify a crime.

While the exploration of the “perfect crime” is timeless, the more compelling aspect of Leopold and Loeb’s story—and the one that keeps inspiring adaptation after adaptation—is the relationship between the two men. What would their trial look like today? Would their sexuality even be allowed to enter into evidence? While it wasn’t clear to many in 1924, through today’s lens, it’s easy to see that Leopold and Loeb didn’t become murderers because they were gay. They were murderers already—they just happened to also be gay.

For more of Courtney Hardwick’s fascinating QUEER CRIME series click here.

Ruby lee / 07 August 2023

We are all worthy of respect love and hyumanity