It’s been 20 years since the 1998 murder of the Wyoming college student – what does his death say to us today?…

I’ve thought a lot about Matthew Shepard over the years. It’s been 20 years since the murder of the first-year University of Wyoming student but I still have trouble wrapping my head around his death, how it affected me then, and how it continues to affect me to this day. The pain hit countless people around the world, and the events surrounding his murder continue to have an impact today because his story began a conversation about hatred and LGBTQ+ rights everywhere.

On the night of October 6, 1998, two men (Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson) lured Matthew from the Fireside Lounge in Laramie, a town of 25,000 near the Wyoming-Colorado border, and drove him to a remote rural area on the eastern side of Laramie. McKinney apparently told Matthew, “We’re not gay and you’re going to get jacked,” before they proceeded to rob, pistol-whip, torture and bludgeon him, tying him to a rough-hewn wooden buck fence and leaving him to die.

At 6 pm the next day, Aaron Kreifels, a passing cyclist, was riding past a new housing development and onto a dirt path in Wyoming’s rugged countryside when he noticed something out of the ordinary. “At first I thought it was a scarecrow,” Kreifels later told the Denver Post, “so I didn’t think much of it. Then I went around and noticed it was a real person. I checked to see if he was conscious or not and when I found out he wasn’t, I ran and got help as fast as I could.”

The “scarecrow” was Matthew, although he hadn’t actually been strung up like a scarecrow, which has been widely reported through the years. He lay on his back unconscious and drenched with blood, his head propped against the fence, legs outstretched. His hands were bound together behind his back with white clothesline from McKinney’s truck and tied barely four inches off the ground to a fencepost. When Kreifels found him, he had been there for 18 hours in below-freezing temperatures after suffering 18 blows to the head and face. He had lacerations on his neck, head and face; a damaged brain stem; and four skull fractures to the back of his skull and the front of his right ear. His shoes were missing.

Reggie Fluty, the sheriff’s deputy who answered Kreifels’ call for help that evening, would later state that at first she thought Matthew could have been no older than 13 because he was so small. She would later describe his face, which was covered in blood, except where it had been partially cleansed by his tears – an image that continues to be referenced in countless essays, poems, and songs dedicated to his memory.

Attending physicians at Ivinson Memorial Hospital ascertained that Matthew’s head injuries were grave and they had him immediately transported 105 kilometres to Poudre Valley Hospital in Fort Collins, Colorado, where he was admitted to the intensive care unit. However, the substantial trauma meant doctors were unable to perform surgery.

Matthew’s parents, Judy and Dennis Shepard, were immediately notified and travelled to Fort Collins from Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, where Dennis worked as an engineer. By the time the Shepards reached Poudre Valley, the story had taken over the headlines and the news media were keeping a 24-hour watch outside of Matthew’s hospital room, where he lay unconscious. The national discussion of the attack initially centred on the legal issue of hate crimes, but as his story began to resonate with people of all sexualities around the world, especially in North America, something changed. The boy who was clinging to life in a hospital bed became a symbol of violence against the LGBT community, a symbol that couldn’t be ignored.

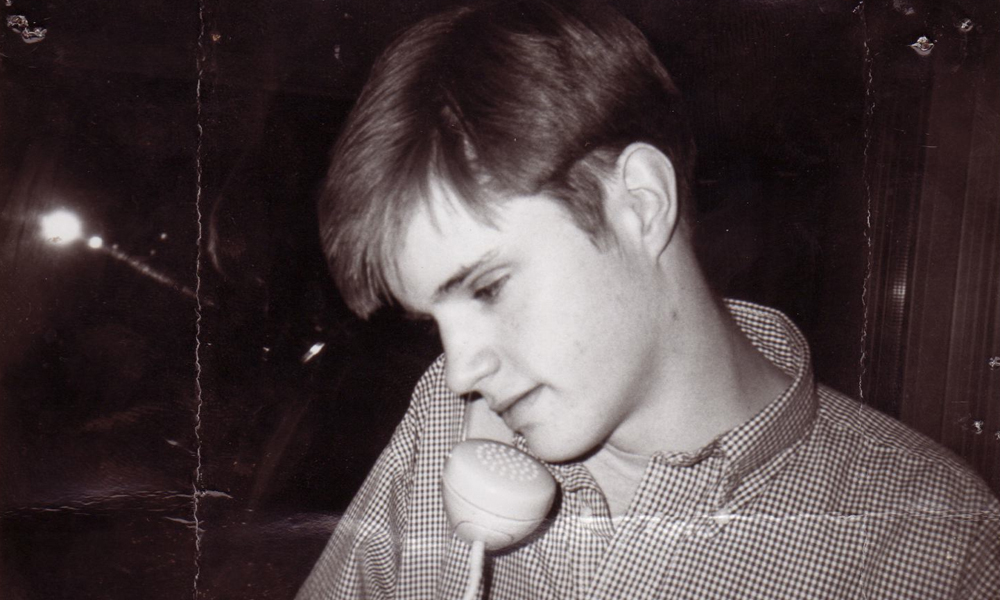

I was just coming out as I sat glued to the TV, watching every channel air footage of the candlelight vigils and the pundits commenting on then President Bill Clinton’s wishes to the Shepards. The story was so closely followed that a website set up by the hospital to give updates about Matthew’s condition eventually drew more than 815,000 hits from around the world. Family-supplied photos of Matthew’s face appeared on every television channel, accompanied by Fluty’s heartbreaking description of his now brutally disfigured face. I watched along with the rest of the world. I was devastated and confused. I saw a lot of myself in him.

Matthew appeared so vulnerable in every image. With shaggy blond hair, braces and a pensive smile, he stood five foot two and weighed just over 100 pounds. I was young and shy, tiny at that point, barely hitting 115 pounds. I was still figuring out who I was and what it meant to be gay. I was only out to some of my friends, and I was filled with questions and what felt like an unbearable amount of shame. So as I obsessively watched CNN, I felt it. Every time Matthew’s image flashed on the screen, it felt like a punch in the stomach.

I saw myself as Matthew Shepard and was angry and broken, as were so many around the world.

Matthew never regained consciousness, and was pronounced dead six days after the attack at 12:53 am on October 12, 1998. He was 21 years old.

“We were with him when he died,” Judy said.

• • •

Matthew’s funeral was on October 16, 1998, at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Casper, Wyoming. It was a complete circus for so many reasons, and Matthew’s parents and his younger brother, Logan, were given little space to privately grieve. Judy and Dennis issued tickets to ensure that only friends and family were allowed into the church the day of the service, while other churches in Casper (the family’s hometown) offered space to accommodate the overflow.

Matthew’s funeral is significant not just because we were watching a family publicly grieve for their slain son, but because it marks arguably the first occasion we were bombarded with images of pure hate, courtesy of the Westboro Baptist Church, a tiny Kansas congregation. Their leader, Fred Phelps – a defrocked minister, and author of the Internet site GodHatesFags.com – led his handful of protestors (along with another anti-gay protester, W. N. Otwell of Enterprise, Texas) to Matthew’s funeral, where they carried signs that read “God Hates Fags” and “Matt In Hell.”

As a young, partially closeted gay man, those broadcast images were terrifying to me. The anti-LGBT protestors may have been across the street penned inside black plastic barricades, but they weren’t shy about taunting the huge crowd of mourners. Television cameras weren’t shy about capturing and airing the footage, either. (Amateur and news footage of the scene outside Matthew’s funeral can easily be found on YouTube.)

To counter the protest, Matthew’s friends and supporters dressed as angels and, to protect the Shepard family from hearing or seeing Phelps and the Westboro Baptist Church, the assembled crowd sang “Amazing Grace” to drown out his anti-gay preaching.

Judy said later that she never saw them. “They took us through a door in the back of the church.” Police asked Dennis to wear a bulletproof vest under his shirt when he spoke at Matthew’s service, and deployed snipers on surrounding rooftops.

Elton John sent flowers to Matthew’s funeral; Ted Kennedy and Ellen DeGeneres spoke out on the steps of the US Capitol Building; Barbara Streisand phoned the County Sheriff’s office to demand quick action on the case; and Madonna called the University of Wyoming to voice her concerns about what had happened.

• • •

The trials of McKinney and Henderson were also a media circus.

The pair had been arrested while Matthew lay unconscious in intensive care at Poudre Valley. They had returned to Laramie that same night and got into a fight with some other men, which attracted the attention of the police. When Officer Flint Waters arrived at the disturbance, he apprehended Henderson and, while searching McKinney’s vehicle, he came across a blood-smeared gun as well as Matthew’s credit card and his shoes. McKinney and Henderson were charged with aggravated robbery, kidnapping and attempted murder.

When Matthew succumbed to his injuries in the early morning hours of October 12, the charges against the two were quickly upgraded to felony murder and kidnapping. If convicted, both could receive the death penalty. Their girlfriends were charged with being accessories after the fact.

Henderson’s case moved forward first. In April 1999, he reached a pre-trial plea agreement, which took the death penalty off the table in exchange for two consecutive life sentences. McKinney’s case proceeded to trial in the fall, a year after the attack. His effort \to mount a “gay panic defence” was ruled out by Judge Barton Voight; after that, McKinney’s counsel, prosecutor Cal Rerucha and the Shepards agreed to a similar plea bargain for consecutive life sentences and McKinney’s agreement not to speak to the media about the case (a provision he would repeatedly violate in later years).

I wasn’t out to my family at the time, so I remember paying close attention to the family’s reaction, in particular Matthew’s father.

Addressing McKinney in court before his sentencing, Dennis told him that although he didn’t oppose the death penalty, he was “going to grant you life…because of Matthew.”

“I would like nothing better than to see you die, Mr. McKinney. However, this is the time to begin the healing process, to show mercy to someone who refused to show any mercy…. Mr. McKinney, I’m going to grant you life, as hard as that is for me to do, because of Matthew. Every time you celebrate Christmas, a birthday, or the Fourth of July, remember that Matt isn’t. Every time that you wake up in that prison cell, remember that you had the opportunity and the ability to stop your actions that night…. Mr. McKinney, I give you life in the memory of one who no longer lives. May you have a long life, and may you thank Matthew every day for it.”

Both Henderson and McKinney were incarcerated in the Wyoming State Penitentiary in Rawlins.

Dennis would later publicly wonder whether there was some kind of purpose to his son’s death, saying, “Maybe it was meant to be. He was meant to change the world.”

He did.

• • •

In the years since the trial ended, there have been more twists to Matthew’s story, more painful blows to the LGBTQ community. In 2004, 20/20 broadcast a segment complete with statements from Henderson and McKinney claiming the homicide had occurred not because Matthew was gay, but because of a drug-related robbery gone wrong. Stephen Jimenez, the producer of the segment, would go on to publish The Book of Matt: Hidden Truths About the Murder of Matthew Shepard in 2013. He asserted that the murder was not a hate crime, but could instead be blamed on crystal meth, a drug that was flooding the scene at the time. He also claimed that McKinney and Matthew had a friendship and had been engaging in casual sex.

Jimenez’s theory has, understandably, caused a lot of anger and has drawn criticism. I remember going on a social media rampage, fuming at the largely unsubstantiated claims. For the record, most critics strongly reject the book as being poorly researched, and McKinney has never acknowledged that he even knew Matthew.

The Matthew Shepard Foundation, which was launched on December 1, 1998 – which would have been Matthew’s 22nd birthday – also stands firm on the murder being fuelled by homophobic hatred. The not-for-profit organization has been an instrument for social change in the last 20 years. It fuelled a movement. It fuelled activism. It encouraged me to come out to everyone in my life.

“While Matt was in the hospital, people from all over the country and even the world sent us letters, teddy bears and money. They were urging us to use the moment to make an impact,” Judy told me recently. “With all eyes on our family, we listened to the public and started the Matthew Shepard Foundation. Our goals are to erase hate and replace it with understanding, compassion and acceptance.”

A year after Matthew’s murder, then President Bill Clinton urged the US Congress to expand the list of hate crimes covered under federal law to include cases involving sexual orientation.

“The Hate Crimes Prevention Act would be important substantively and symbolically to send a message to ourselves and to the world that we are going into the 21st century determined to preach and to practise what is right,” Clinton said at the time.

In Clinton’s proposed hate crimes legislation, the law would be expanded so the Justice Department could prosecute crimes based on a person’s gender, sexual orientation or disability. At the time, only crimes based on a victim’s race or religion could be prosecuted as hate crimes.

No such legislation passed during Clinton’s presidency, which ended in 2001. But Matthew’s murder became a symbol of the hatred many lesbians and gay men face, and his death was helping to change the conversation about the LGBT community and their rights.

Motivated in part by the hate-crime legislative debate, Judy established herself as a prominent LGBT rights activist, and played a key role in finally securing passage of a federal LGBT-inclusive hate crime bill. The Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr., Hate Crimes Prevention Act, also known as the Matthew Shepard Act, was finally passed by Congress on October 22, 2009, and signed into law by then President Barack Obama on October 28, 2009, 11 years after the crime.

“In the past 20 years, one of the most memorable moments was when Dennis and I joined President Barack Obama at the White House,” Judy told me. “After nearly a decade of lobbying and advocating for federal hate crimes legislation to inclue language for sexual orientation and gender identity, we finally saw that happen with the signing of the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr., Hate Crimes Prevention Act. But that was only one success out of many we’ve had over the course of the last two decades. I think that Matt and his story opened up the country to having a conversation about hatred and LGBTQ+ rights.”

It’s true. Judy and the Matthew Shepard Foundation have been an instrument for change and social progress since the Foundation’s inception.

One of the initiatives it got involved in is the play The Laramie Project. Shortly after the murder and after Henderson and McKinney’s incarceration, members of New York’s Tectonic Theater Project began visiting Laramie. Over the course of 18 months, they recorded interviews with hundreds of residents on what had happened to Matthew, and turned that into the play The Laramie Project, which debuted in 2000. The three-act play sees eight actors take on nearly 60 different roles. When it first played in Toronto at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre, I saw it twice.

“The Shepards were integral in helping pass the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr., Hate Crimes Prevention Act,” Sara Grossman, communications manager at the Matthew Shepard Foundation, told me. “But the Matthew Shepard Foundation also does a lot of outreach and helps with local productions of The Laramie Project. From North Dakota to South Korea, we have had our hands in hundreds, if not thousands, of productions over the last 18 years [since the show debuted]. In the last two years alone, 350 productions have gone up around the globe – and those are just the ones we know about!”

Of course, the Matthew Shepard Foundation’s work goes far beyond the award-winning play.

“We also have a by-and-for-LGBTQ+ youth blog called Matthew’s Place, which is a great source of information for youth, their families and friends, or anyone who wants to learn about the lived experience of LGBTQ+ youth,” Grossman told me. “We go into communities that need training for law enforcement on how to report and prosecute hate crimes. We choose these communities by determining where there is a high number of hate crimes, or if there is an area where we know there are hate crimes but no reports. Building a bridge between law enforcement and the victim communities is also an important part of this work.”

• • •

On December 1, 2018, Matthew Shepard would have turned 42 years old. In the 20 years since his murder, we have watched as his legacy has expanded in scope and grown in influence, helping to inspire a growing acceptance of gays and lesbians into the mainstream. Because of Matthew, we have laws, poetry, theatre, and even full lesson plans dedicated to erasing hate from our schools. I would like to think he’d be proud of the work his parents and the Foundation did in his honour.

But, despite his martyrdom, it should be noted that there is no substantial memorial to Matthew in Laramie. The wooden buck fence where he lay dying for 18 hours? It has been torn down and there is no marker in its place, only wild grass.The Fireside Lounge – where Matthew was lured away by McKinney and Henderson – is also gone, sold and renamed years ago.

“In contrast with Pulse [nightclub] in Orlando, which has several memorials and works of art dedicated to the victims, there is only a single bench in Laramie on the University of Wyoming campus dedicated to him,” Grossman told me. “There is nothing else.”

• • •

So how far have we really come?

“I didn’t think we’d still be doing this work today,” Judy told me. “But, she made clear, progress has been made. “Two decades ago, the majority of the country was homophobic. Generally, phobias and fears are rooted in a lack of education. LGBTQ+ people weren’t out back then, so people didn’t know gay people. It’s so much harder to hate a person than a concept. The more people who came out over time, the less homophobic the landscape became. It’s definitely less harsh for the community in Laramie now, as it is in the rest of the country. They’ve seen a lot of progress since Matt was killed.”

The progress is undeniable. Matthew’s death put a face on hate-filled tragedies and became a watershed moment that forever changed the conversation about the LGBT experience. It changed the way I saw myself. Seeing Matthew Shepard become a symbol of violence against the LGBT community, just as I was figuring out who I was, forever changed me. Through the years Matthew’s story has haunted me, and in recent years it’s reminded me of a responsibility to tell the stories of LGBT people.

His legacy is important to me. So I asked Judy about Matthew’s legacy. She paused before talking about the attention at the time, and how, in the years since, Matthew’s story continues to stay relevant – mostly because she refuses to let the world ignore it.

“From the youth we engage with and interact with, we always find that young people strongly connect with Matthew’s story and his impact,” Judy told me. “He was a fervent supporter of human and civil rights around the world. He struggled with depression and loneliness. He had triumphs and failures. He was incredibly human, certainly not without flaws, and sought to find love and happiness in his life, work and studies, like many of us do. Young people are inspired by his story and aspire to continue on his path in honour of him.”

“The significance in Matthew’s death and the impact it had on the world in 1998 was about much more than who Matt was as a person or an individual, but more representative of a society’s treatment and abuse of the LGBTQ+ community. For decades, gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender people had been harassed, abused and killed for being who they are. Matthew became a figurehead for the ‘people we knew,’ our neighbours, co-workers, classmates, friends and family. People could no longer dismiss the violent actions as happening to ‘others.’

“Matt was a normal, average college student who was brutally attacked and killed for being gay. His death marked a tipping point for the LGBTQ+ community, and sparked a new movement and generation of activists who refused to stay silent about it, and non-LGBTQ+ people could no longer ignore the harsh realities this community faced.”

This. This will be his legacy.

CHRISTOPHER TURNER acted as guest editor for this issue of IN magazine. He is a Toronto-based writer, editor and lifelong fashionisto with a passion for pop culture and sneakers. Follow him on social media at @Turnstylin.

Dominick Caron / 08 November 2018

I still remember this as if it happened yesterday!

I recall watching a docs on Netflix about young Matthew Sheppard.

So So sad!

Dominick Caron