This former hockey pro is making sport a better place for LGBTQ athletes…

“For years I lived a life of denial because I am gay.”

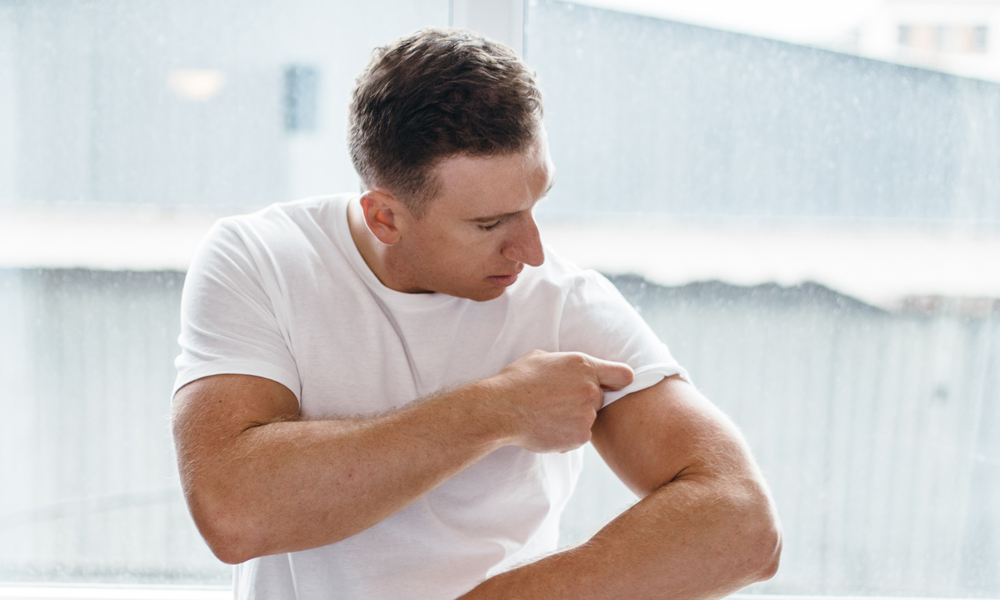

Brock McGillis made waves in November 2016 when he wrote those words, becoming the first professional hockey player to publicly reveal he’s gay. After many years playing with the Ontario Hockey League (OHL) and for minor leagues inEurope and the United States, he wrote a first-person piece for Yahoo Sports Canada. Within 24 hours he’d received more than 10,000 messages of support.

It was a life-changing moment for the Sudbury native. “It blew me away,” he says. “I just kept crying.” Since then, McGillis has become an outspoken advocate for the LGBTQ community. He regularly travels across Canada speaking about inclusivity to school groups and organizations. Today he’s very much out and proud, but the road to get there was far from smooth.

“Growing up in Northern Ontario I was the typical hockey boy,” says McGillis. He loved the game, and spent hours on the ice practising. Drafted to the OHL in his teens, he was a celebrity in his community. “I was a cocky jock who got a lot of attention.” Outwardly, it was the best time of his life. Inside, he was a mess.

McGillis says he knew he was gay as a young child. He vividly remembers asking his parents about it when he was six years old. They responded that if he was gay, that was fine and they loved him. But, immersed in the macho world of hockey, it was another story. “Men tend to feminize one another or use homo negative language to put each other down,” says McGillis. “If you’re a ‘fag’ or a ‘woman,’ you’re [considered] less than a man and not tough enough for our sport.” So he kept his feelings to himself, and by age 16 was drinking heavily to numb the pain.

At age 19, McGillis was ranked on the NHL draft list, but his prospects were derailed by a series of injuries, from cuts and concussions to mono and knee surgeries. In the years that followed, he continued to play but was anxious and depressed, and he attempted suicide several times. “I hid [who I really was] from everyone. And I hated myself.” At 23, while playing hockey in Europe, he “was taking a lot of risks and doing some foolish things,” he says. “I knew that if I didn’t do something, I would die.” It was a turning point. When the season ended, he returned to Canada and decided to go on a date with a man. “It was the scariest experience of my life. I was shaking.” Soon after, he fell in love and remained in a serious relationship for three years. And yet, still, he didn’t come out to his family or his teammates.

McGillis refers a lot to “the culture of hockey,” a landscape he describes as hyper-masculine and extremely homophobic. But it was the only world he knew and one he wasn’t sure he wanted to leave. In the hockey community, he says, “people expect you to act a certain way, and I conformed to that.” He was scared that if anyone knew he was gay, he would be shunned from the game. He was terrified that if his parents knew, they might accidentally let it slip.

“The majority of hockey players come from North America and Western Europe,” he says. “These are some of the most inclusive countries in the world and yet it seems like it’s the least inclusive sport. It boggles my mind.” Part of the reason McGillis thinks attitudes have been slow to change is because “players become coaches and those same coaches go on to become managers,” he says. “Men in their 50s and 60s [have been] using the same language for years and their archaic views have remained intact.”

Plagued by injuries and emotionally exhausted, McGillis decided to take a break from the game. “The minute I stopped playing, I felt free, like my life was about to start.” He spent time with his boyfriend and hung out in the village, but didn’t really feel part of the community. Publicly he continued to pose as “this hetero hockey player, because it was how I self-identified,” he says. “When you’re an athlete at a high level, that’s all people talk to you about, and it’s all you know yourself as.”

When he was 25, McGillis was invited to play for the Concordia University team. Back in the hockey world, he told his long-term boyfriend that he’d need to “keep up appearances” by dating women. Now, he is filled with regret about this period in his life. “It breaks my heart that I did that to somebody I cared so much about,” he says. ““Not only will I keep you a secret, but I’m not going to be faithful.’” The relationship did not survive, and it was a lonely time for McGillis. “I was grieving the loss of the first person I truly loved and [because no one knew about it] I had nobody to talk to.”

The catalyst for real change in McGillis’s life finally came in 2009 while he was watching a Maple Leafs game on TV. A young man was speaking between periods about being gay. It was Brendan Burke, an aspiring general manager and son of Calgary Flames President Brian Burke. McGillis reached out to Brendan, and a strong friendship formed. “It was a relief, like 100 pounds off my shoulders,” he says. “I finally had someone in my life who knew I was gay but who also understood what it was like to be in the hockey world.” In February 2010, Brendan sent McGillis a text message that said, “I can’t wait for the day when you’re out to your family like I am to mine.” Two days later, Brendan tragically died in a car accident. His final words resonated with McGillis. Soon after, he came out to his brother – a fellow OHL player – followed by the rest of his family and close friends.

After yet another knee injury McGillis retired from playing hockey, and he started working as a coach and mentor to young players in and around Sudbury. Professionally, he kept his sexuality to himself. “In smaller communities there’s not a lot of exposure to the LGBTQ community,” he says. “What would the parents think? Would they want their sons and daughters around the gay guy?” There started to be rumours, and one of the hockey associations he’d been working with abruptly let him go. “All my worst fears had come true,” says McGillis. “I was being shunned from the community that I love.” But he kept working with young athletes, and one day he got a call from a hockey mom asking if she could set him up on a date. “I said to myself, ‘Oh no, what do I say?’ Finally I say, ‘What’s her name?’ and she answers, ‘His name is Steve.’” McGillis asked the parent how she knew he was gay. “All the boys know,” she said. “They’ve known for years.” The hyper-masculine hockey world was evolving, just a little. “These cocky little hockey boys who think they’re gifts to the world all know I’m gay and choose to work with me. In northern Ontario. How cool is that?”

McGillis started to notice that if any of his players used homophobic language, they’d immediately apologize. “I wondered if maybe it’s because they know me. Maybe they still go to school and call kids fags.” Then he heard that one player was making his friends at school do 50 push-ups any time one of them said, “That’s so gay.” Says McGillis: “It made me realize that if a shift can happen in my tiny bubble, maybe it can happen on a larger scale. But I was still afraid [to come out]. I’d been treated so poorly by a division within the hockey world, [and] what if it got worse?”

Then the Pulse nightclub shooting happened, and McGillis’s entire view on things changed. “I was angry and afraid. It could have been me and my friends in Toronto. It gave me the kick in the ass I needed. I said, ‘I’m done. I don’t care what it costs me, I’m using my platform and doing whatever I have to do.’” He reached out to a journalist he knew at Yahoo Sports, penned a letter and, finally, at 33 years old he was “officially” out of the closet.

McGillis refers to his post as “an f-you” to what had gone on in Orlando. “I just wanted to maybe help one person. I had no idea before that there were so many people struggling like I had been.” Now, after so many years keeping quiet about his sexuality, the former hockey goalie can’t stop talking. He reckons that in just 18 months he’s spoken to over 100,000 people including high schools, businesses and OHL teams.

His goal? To shift the homo-negative and feminizing lingo that’s still so prevalent in sport. “We’ve become desensitized to the language because it’s so frequently used,” he says. “Just recently I had a coach tell me that when you give up the puck in your zone through the middle of the ice, he calls it ‘Queer Street.’” And, during the 2017 playoffs, an NHL player called a ref “cocksucker.” When McGillis spoke out calling the comment personally offensive, he received death threats. “If this language is impacting me, what’s it doing to the closeted kid who’s being directly bullied?” he says. “It perpetuates a [homophobic] culture.”

After so many years living in pain, McGillis says he’s the happiest he’s ever been. “This past year has been exhausting in the best way possible,” he says. “I never thought I’d be the first [professional hockey player] to share my story. I thought there’d have been others before me, but it didn’t turn out that way.”

This fall he’ll be featured in a book about hockey heroes who are changing the game for the better. There’s a YouTube series, and he’s one of three people being profiled in a National Film Board documentary about LGBTQ+ athletes. He’s also starting a foundation and hoping to speak at every elementary and high school in Canada. “My goal is to be at the forefront of a shift in society where we recognize our differences and celebrate them, as opposed to trying to conform.When I talk to kids, I say, ‘Normal doesn’t exist. It’s a fallacy. We’re all a bunch of weirdos and it’s beautiful.’”

MARIANNE WISENTHAL is a Toronto-based writer and content strategist. When she’s not wrangling words with aplomb, you can find her singing show tunes with her community choir.

Gavin Coulthard / 27 March 2022

Brock, in a culture full of pricks, you’ve got the biggest balls of them all. Koodos to you brave man.

— A straight guy with a queer eye.

PS: Did you go on the date?

Katerina Stavrides / 01 September 2018

Very interesting and well written.