His life makes for an intriguing story. McQueen reveals an intimate portrait…

Eight years after his untimely death, Lee Alexander McQueen has never been more revered. Few understood Britain’s most accomplished (and controversial) fashion designer during his lifetime, which is probably why we continue to be captivated by the life of the sensitive visionary who reinvented the world of fashion before he took his own life in 2010.

In April, a brand–new documentary, entitled McQueen, premiered to rave reviews at the Tribeca Film Festival, aimed to preserve and honour the openly gay designer’s life and legacy. The documentary spans the breadth of McQueen’s fashion career, from his graduation from the prestigious Central Saint Martins design college in 1992, to his appointment as the bad boy creative director of Givenchy in 1997, his departure from the French fashion house in 2001 and the final years he dedicated to his eponymous label before his suicide. The film hits theatres this summer.

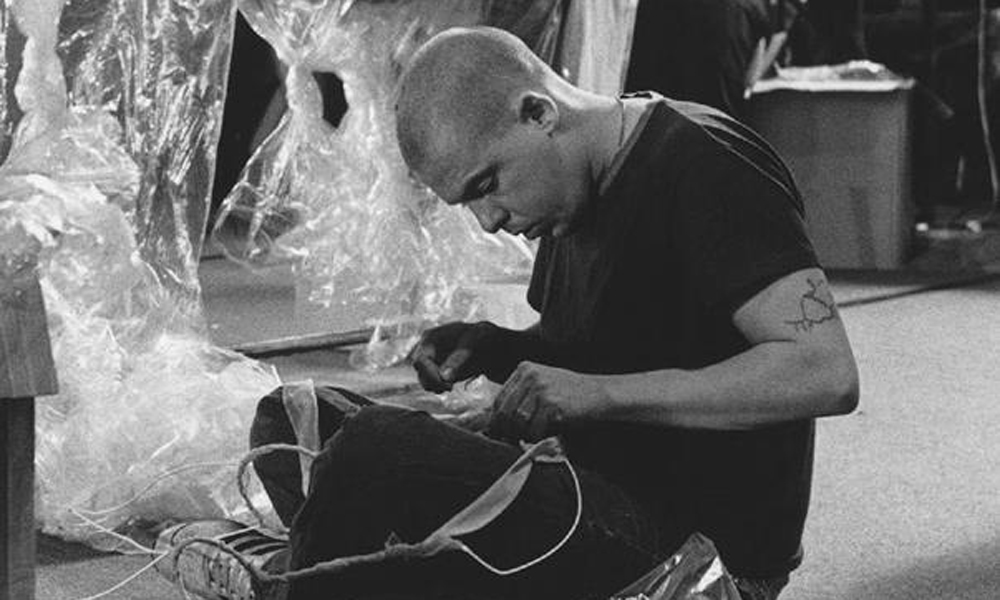

Directed by Ian Bonhôte and Peter Ettedgui, McQueen packs an emotional punch revealing the legendary, albeit troubled, designer through a compilation of clips of his cinematic runway shows, never-before-seen archival footage, and interviews with McQueen’s colleagues, mentors, ex-lovers and family members.

“We wanted to make a really respectful cinematic version of Lee’s story,” Bonhôte said. “You could go very tabloid and sensationalist, but we wanted to put his work at the film’s centre, and to try to tell his life from the fashion shows. People were excited about this.”

In the years since his death, McQueen has become one of popular culture’s battlegrounds, as fashion biographers attempt to piece together a picture of the man behind the designs. It almost seems as though McQueen anticipated this. During his life, he created and cultivated a very specific public persona: he was the son of a cab driver and a schoolteacher who struggled with his weight, his self-image and his sexuality. He grew up on the ‘wrong side of the tracks’ and against all odds became a tailor’s apprentice on Savile Row before being accepted to Central Saint Martins. In 1992, the famously eccentric fashion editor Isabella Blow spotted and purchased his entire graduate collection (named “Jack the Ripper”) for £5,000, and then helped him launch his eponymous label, turning him into a fashion world darling. At age 27, he was appointed head designer at Givenchy, much to the outrage of the French fashion press—and while his time at the fashion house was brief, and notoriously rocky (McQueen once described his tenure at Givenchy as “like taking a dinosaur out of the sea,” according to Blow), it helped propel him to fashion superstardom. He won countless awards (including British Designer of the Year in both 1996 and 1997) but never lost his brash East End accent and street-savvy wit.

As his fame grew, so did his ego and the number of drug-fueled outbursts. He lost a dramatic amount of weight and had plastic surgery. And then there was his complicated relationship with Blow, his dysfunctional romantic relationships and the drug-induced rages during his final years. He turned himself into a cult figure, one of the most extraordinary visionaries the fashion industry has ever known. And then he committed suicide on the eve of his beloved mother’s funeral. Lee Alexander McQueen was found hanged at his London home on February 11, 2010. He was 40 years old.

The film attempts to break away from those talking points and figure out this difficult character through a series of new interviews with those closest to McQueen that give unparalleled insight into his way of thinking.

“The archive footage that the family gave us was incredibly important because it shows him, I think, in a different light,” Ettedgui said.

Footage from family friends—especially footage of a young McQueen—showcases a different, rarely seen, side of McQueen. Videos of him laughing and playing with his dogs paint a new, softer side of the bad-boy designer, while an interview with his late mother describing him as a “sweet boy” is heartbreaking.

“We wanted to make this film very intimate,” Ettedgui explains.

The film is anchored with footage from McQueen’s most unforgettable runway shows: his 1992 student thesis show “Jack the Ripper Stalks His Victims” from Central St. Martin’s, his Fall/Winter 1995 “Highland Rape” show, which featured tattered tartan dresses and a tampon-strewn skirt (the presentation was decried as misogynistic at the time); the Spring/Summer 1999 “No. 13” runway presentation, which featured Shalom Harlow spinning on a platform while two robots spray-painted her white dress; his unforgettable Spring/Summer 2001 “Voss” show that turned the runway into a two-way mirrored insane asylum; the Fall/Winter 2003 “Scanners” presentation that featured his models walking in a wind tunnel; the Fall/Winter 2006 “Widow Of Culloden” runway presentation which featured the infamous Kate Moss hologram; the highly personal Spring/Summer 2008 “La Dame Bleue” presentation, which was a tribute to his late muse and mentor, Blow (who committed suicide in May 2007 after consuming a fatal dose of the weed killer Paraquat); and the designer’s ethereal Spring/Summer 2010 “Plato’s Atlantis” presentation.

“If you leave without emotion, then I’m not doing my job properly,” says McQueen in the film about his runway shows. “I don’t want you to walk out feeling you’ve just had Sunday lunch. I want you to be repulsed or exhilarated. As long as it’s an emotion.”

The runway shows highlighted in the film take on a new emotion, as they are combined with shaky behind-the-scenes camcorder footage captured by co-workers and are essentially narrated by archival interviews with Blow as well as McQueen’s mother, and many of the people who worked most closely with the designer.

“When you tell the story of someone that lived, you tell the story of the people that lived next to him. It’s their story as much as the person’s,” Bonhôte explains.

One anecdote comes from Italian designer Romeo Gigli. McQueen worked as Gigli’s design assistant in 1990, and Gigli recalls making the young designer redo a coat over and over, only to find that McQueen had written “Fuck you, Romeo!” inside the lining after the third iteration.

Countless examples of that bad-boy charm dominate the film.

Golden Globe nominee Michael Nyman (The Piano, Gattaca, The End of the Affair, Ravenous) composed the moody score for the film (Nyman himself was a former McQueen collaborator), while a series of interstitial animations help break the film into chapters using McQueen’s iconic skull motif.

Strangely, in the film’s 111 minutes there is no mention of the designer’s ex long-term partner, filmmaker George Forsyth. He became McQueen’s unofficial husband in 2000 (before same-sex marriages were legalized in the UK), and died shortly after McQueen at the age of 34. Forsyth’s parents deny that their son died of an overdose of the painkiller codeine, and maintain that he had accidentally taken a large amount of the drug after it was prescribed to him as part of treatment for a neurological condition. While the omission of any mention of Forsyth is a troubling oversight, many of McQueen’s other former partners and lovers are interviewed and offer up insight into the designer’s way of thinking and his ongoing struggles accepting his own sexuality.

Fashion fans may also feel off about another blank space from the film. It abruptly ends after McQueen’s 2010 death, with virtually no mention of the ongoing legacy of his namesake label or his successor, Sarah Burton. While plenty of McQueen’s close collaborators were interviewed and appear in the film, Burton is mentioned only once and is never interviewed.

But Bonhôte and Ettedgui explain that Burton’s absence was intentional. The film is meant to focus on the man behind the brand, not the brand itself.

“Had there been a very open channel or communication or co-operation between the brand and us, I think we would’ve probably wound up making a brand film, which was not what we wanted to make,” Ettedgui notes.

For the record, the brand has continued to thrive under Burton’s direction. In 2011, she famously designed Kate Middleton’s royal wedding dress. That same year, people lined up for hours to see Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty, a retrospective of his work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The elaborate retrospective attracted more than 650,000 visitors (one of the most-visited shows in the Met’s history) and included more than 100 ensembles and 70 accessories from McQueen’s 19-year career, starting with selections from his 1992 MA Graduation collection “Jack the Ripper Stalks His Victims,” and ending with pieces from his partially completed Fall/Winter 2010-11 “Angels And Demons” collection. As the label’s creative director, Burton was subjected to merciless and unnerving scrutiny but managed to take the label to new, albeit softer, heights away from its dark past.

In the years since McQueen’s untimely death, there have been countless TV documentaries, exhibitions, a play by British playwright James Phillips (which was unveiled at the St. James Theatre in London in 2015) and half a dozen books bearing his name, all attempting to reveal an intimate portrait of the man and his work. While McQueen doesn’t reveal a full portrait, it does captivate like none of the projects before it.

We may never get to fully know the real McQueen, which is probably what haunts us. And that’s the way the designer would have wanted it.

McQueen hits theatres across the country on July 20, 2018.

CHRISTOPHER TURNER acted as guest editor for this issue of IN magazine. He is a Toronto-based writer, editor and lifelong fashionisto with a passion for pop culture and sneakers. Follow him on social media at @Turnstylin.

POST A COMMENT