Those who don’t know their history are doomed to repeat it (plus, hey, it’s an illuminating – and sometimes fun – read)…

By Rowan O’Brien

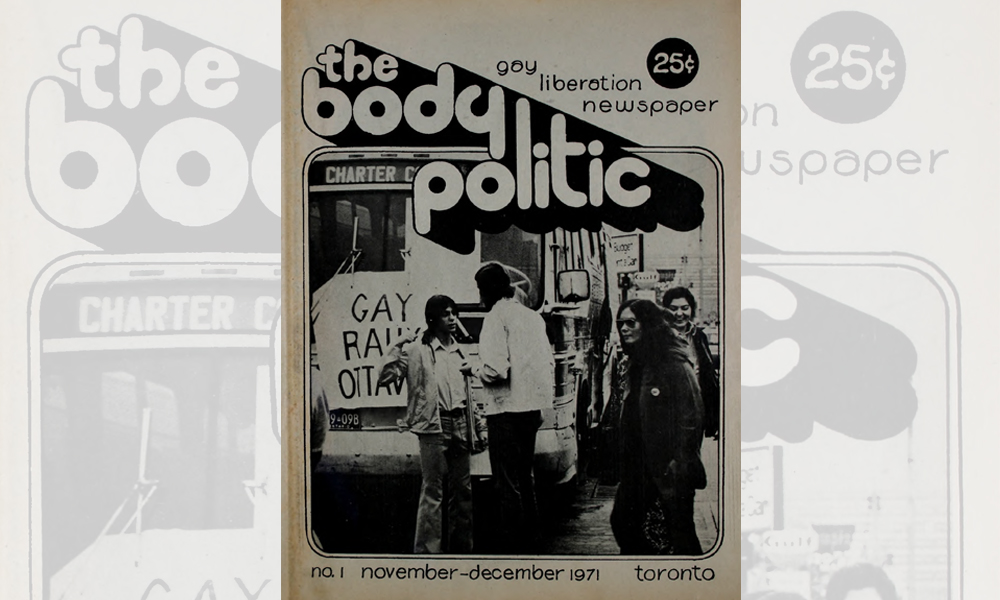

I can still picture the queer studies class where I first heard about The Body Politic, a Canadian monthly LGBTQ magazine that was published from 1971 to 1987. The queer and bespectacled professor stood at the front of an elegant room in a manor owned by the university, reading from an article in the magazine. Although this course was cut short by one of York University’s many infamous strikes, the name of the publication anchored itself in my brain. As a queer “zillennial,” I was aware of The Body Politic’s legacy through my forays into queer Canadian history, but was worried I might never get to read the magazine for myself.

The pandemic was in full swing when I graduated in September, granting me the opportunity to finally read for pleasure and dive into queer history. This desire to connect with queerness was exacerbated by the loss of in-person queer space and the amount of ahistorical information being weaponized in online queer spaces on sites like Twitter and TikTok. Underneath these surface feelings of frustration was a more tangible sense of duty to and admiration of my queer elders. After all, The Body Politic forged a symbiotic relationship with queer Canadian history, where the magazine would report on queer events, thereby influencing the community and resulting in more queer action to report on.

You might wonder what caught my interest about a magazine that ceased publication more than 30 years ago. But it was more than just historical interest: it is important for young queer people to read these magazines because, as they say, those who don’t learn from history are doomed to repeat it, and it appears we get trapped in that cycle far too often. The Body Politic is an incredible piece of queer history, and a huge contributor to the progress we’ve made so far – and haven’t made – in Canada.

This collective ran The Body Politic together, with the members voting on the content of each issue. The paper steadily grew and became one of the greatest dispensaries of queer information in the country, but it wasn’t all sunshine and rainbows. In 1977, an article titled “Men Loving Boys Loving Men” by Gerald Hannon landed The Body Politic in hot water, which was already boiling given the sexual assault and murder of 12-year-old Emanuel Jaques by a group of men four months earlier. This led to a police raid at The Body Politic office and the seizure of 12 boxes of material, including subscription lists. This action by the police was widely protested by many, including by Harvey Milk, who held a solidarity rally in San Francisco, according to Donald W. McLeod’s to.ca/bitstream/1807/74702/6/Donald%20W%20McLeod%20Lesbian%20and%20Gay%20Liberation%20in%20Canada%201976%201981.pdf” target=”_blank” rel=”noopener noreferrer”>annotated chronology of gay liberation in Canada.

Because of this article, The Body Politic and three of its members were charged for “possession of obscene material for distribution” and “use of the mails for the purpose of transmitting ‘indecent, immoral, or scurrilous material.” The trial started on January 2, 1979, the beginning of a three-year legal battle, including one appeal and two acquittals, until they were finally found not guilty in April 1982. Unfortunately, the seized materials were not returned until April 1985, eight years after the initial raid. During this time, The Body Politic was also charged with publishing obscene materials when they ran an article about fisting in 1982 by Angus MacKenzie, titled “Lust with a Very Proper Stranger.”

The Body Politic connected queer Canadians and served as a platform for marginalized voices that was missing from mainstream media. It was especially praised for its coverage of Toronto’s bathhouse raids and the global AIDS epidemic. In 1973, the collective created Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives to preserve queer history, and incorporated as Pink Triangle Press in 1975. The Body Politic was resilient, never allowing a bully to strike them down and get away with it. When the Toronto Star refused to run an advertisement for the publication, they took the issue to the Ontario Press Council and won a ruling that the Star’s actions had been discriminatory. In 1982, Toronto City Councillor Joe Piccininni tried – and failed – to get The Body Politic banned from the press gallery.

Unfortunately, The Body Politic printed its last issue on December 16, 1986. It was survived by Pink Triangle Press’s newer queer tabloid, Xtra, which would start to print more political content after the death of its parent publication.

How to find back issues

Learning about the history of The Body Politic only fed my desire to read the words of publication firsthand. I had heard that the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives (now Arquives) had physical copies, but the ongoing pandemic killed the possibility of a research excursion. After a quick exploration of the Arquives website, however, I was able to find PDFs of all 135 issues of The Body Politic by searching “setName:”The Body Politic fonds”” in their Digital Collections. Later, I would also discover that the Canadian Museum for Human Rights had uploaded all the issues of The Body Politic to Archive.org as PDFs, though they are available to download in many different forms such as ePubs or Kindle files.

These magazines give “queer temporality” a whole new meaning, acting as a time machine for modern-day queer readers. As a York alum, one of the first items that caught my eye was an advertisement for the “York University Homophile Assoc. Dance” in the first issue, followed by an article in the second issue about a new “York Homophile Studies Course” at the university. There’s an endless amount of content to explore, but you might be particularly interested in reading a first-person account of Toronto’s bathhouse raids in a Hannon article titled “Taking It to the Streets,” from the 71st issue. McQuinn’s timeline also draws our attention to an article in the 77th issue by Bill Lewis and Randy Coates titled “Moral Lessons; Fatal Cancer” about how the rare Kaposi’s cancer had suddenly been found in a number of gay men, which we can now recognize as the beginning of the AIDS epidemic.

If you’re looking for articles that are more light-hearted or uplifting, you can check out the 10th issue, which describes one of the first Canadian festivals organized around gay pride in “1973’s Gay Pride Week: A National Event,”which also serves as a reminder that pride has always been political. The 78th issue has a small article called “Dykes Against the Right” by Anna Marushka, which recounts a demonstration that would evolve into the annual Dyke March. If you want a good laugh, find “Hetero Hanky Code” by John Allec a.k.a. Prof J Allec in the 94th issue, or “The Night Before Kitsch-Mas” by Vinn Wilfred in the 133rd issue.

Every issue has a community page, which in the era before Facebook groups allowed queer people to see where they could connect with other members of the community. By the eighth issue, the magazine was printing classified ads that read very similarly to the Tinder and Grindr bios of today. If you’re a creative, I know you will find some inspiration for your next collage or poem in these pages rich with colourful text and old-school “memes.” Leafing through all 135 issues can seem like a daunting task at first, so I recommend using the online index of the articles in The Body Politic provided by the University of Waterloo on their website.

I love Archive.org because it allows you to search the entire collection for keywords, so if you want to read about the bisexuals of times past, for example, all you have to do is search “bisexual” in the text contents. However, be warned that because language and presumptions regarding gender and sexuality are always evolving, some items might have outdated terminology or ideas that make them difficult to read.

It is somehow both validating and frustrating to see the issues we’re dealing with today – whether from society or within the community itself – reflected in these pages. In the article “Out of the Closet & Out in the Cold” from the 110th issue, Danny Cockerline discusses femmephobia, racism and misogyny in regards to gay bar door policies. A quote from this article, which I think is equally important today, reads, “Invisibility is the inevitable result of any move to sanitize the image of gay people in order to make us palatable to straight society. The strategy of ‘good’ gays policing ‘bad’ gays must be seen for what it is: a recipe for self-oppression that offers all of us – the ‘respectable’ and the ‘dirty and perverse’ alike – the quickest route to the closet.”

When reflecting on our past journey, it is important to recognize where we can improve in order to achieve liberation for all. Unfortunately, the publication itself was not free from the oppressive behaviours described above. Most members of the collective were white men, and that didn’t leave a lot of room for diverse voices in the decision-making processes. The paper was very male-oriented, especially in the earlier years, and a paper by David S. Churchill, “Personal Ad Politics: Race, Sexuality and Power at The Body Politic,” discusses the racism not only in the content of the paper, but within the collective as well.

Reading these magazines is a great opportunity for the younger generation of queer people to learn more about their history, as well as the perfect vehicle for older queer people to take a drive down memory lane. Learning from both our past mistakes and past successes can provide an excellent road map for the future of the queer community as we strive towards equity and liberation. In these times in particular, it is easy to feel alone, but reading the words of queer people from 40 years ago is a great reminder that there are others like you everywhere, even if you can’t meet them in person.

![]()

To view the full catalogue of The Body Politic, you simply have to go to https://collections.arquives.ca/ or https://archive.org/details/canadianmuseumforhumanrights. Enjoy!

—

ROWAN O’BRIEN is a queer writer and filmmaker based in Toronto who loves ranting about LGBTQ+ representation in media while creating their own queer stories. Their queer coming-of-age short film CRUSHED played at the Toronto Youth Shorts festival, and their next short film, City Limits, will be released this year.

tomag/docs/in_magazine_may_june_2021?fr=sNDQ0YTIxNzAwODQ” target=”_blank” rel=”noopener noreferrer”>

POST A COMMENT