Collins’ original response to the criticism and his apology after speaking out in defence of the show’s controversial final scene between Dean and Castiel is only part of the problem…

By Steven Greenwood

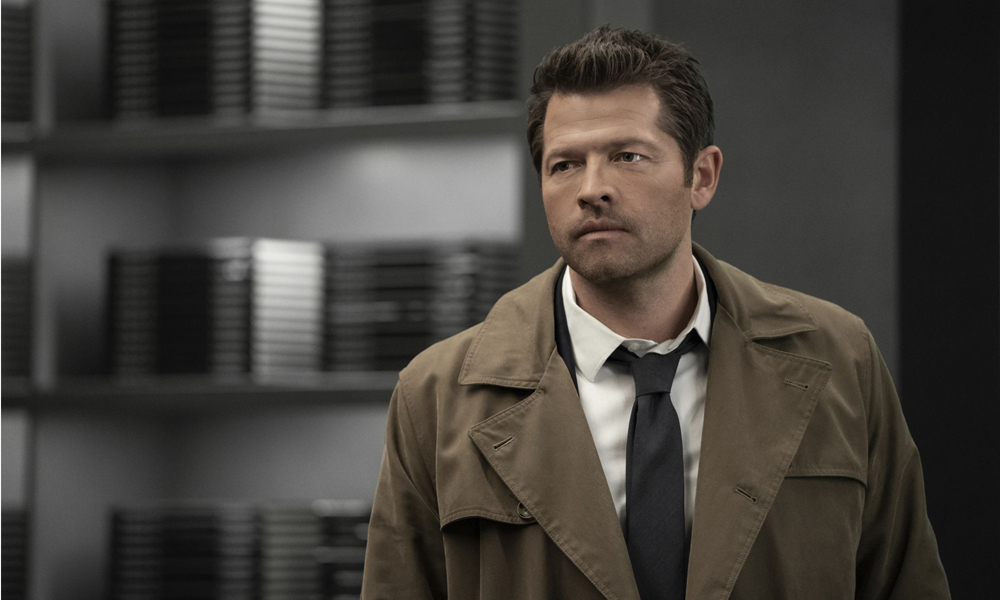

In response to fan criticism of popular TV show Supernatural’s issues with queer representation, Misha Collins posted a Twitter thread on November 26 where he attempted to defend the series’ choices. In this article, I focus less on the specific debates surrounding Supernatural in particular (which aired its season finale recently on November 19), and more in looking at part of Collins’ response itself as a microcosmic example of a larger issue with television production: the over-reliance on fan culture as an excuse for lazy representation.

After initially attempting to defend issues with Supernatural‘s ending – which have been well-documented elsewhere, and include sending a character to “super hell” after he declares his love for another man – Collins began to acknowledge that there were issues with the series’ ending. He posted two comments that exemplify what has become standard practice for professionals working in television when confronted with poor attempts at representation.

The first comment: “I’m confident you guys can sort that part out as your writing, art, and imaginations play the story out past the last frames we filmed.”

The second: “If it’s not too much to ask, please tell me what we could have done better.”

Both of these comments place the bulk of work on fans of the series to make up for its shortcomings with representation. The first focuses on fanfiction and fan art as an avenue where fans can flesh out storylines that the series underdevelops, and the second asks fans to reach out to producers with advice on how to improve representation.

On the one hand, Collins’ recognition of the power of fan fiction and audience response is affirming. Queer readings of mass culture are such an important part of queer history that to tracing the ways that queer audiences have thrived on developing and celebrating the subtext and queer potential of seemingly “straight” texts. To have a major celebrity openly acknowledge this as a valid practice – and one endorsed by those involved in the production of the series – gives validity to an important queer historical practice.

Similarly, the choice to prioritize queer fans’ voices and perspectives – asking (very politely) for advice on how to do better – also has positive potential. Collins acknowledges the need to actually consult with the community that’s being represented rather than assuming what they want, which is a step in the right direction.

However, part of the issue with producers more openly acknowledging fanfiction is what has become an overreliance on it as a way to correct a show’s problems, and thus an excuse to become lazy in the quest for representation in the series itself. While Buffy the Vampire Slayer showrunner Joss Whedon famously declaring that fans were welcome to be – well – responsible with the actual writing and direction of the series, since they can rely on fans to do this work for them.

While queer fan practices are, and have always been, an important practice, they need to exist alongside – rather than as an alternative to – the demands for explicit on-screen representation. Producers recognizing the value of fan fiction and the legitimacy of subtext is a good step, but it can’t be used as a replacement for the effort to improve explicit, clear representation.

The other major issue represented here – particularly in reference to Collins’ second comment – is that of financial compensation, and the exploitation of fan labour. A common topic in scholarship surrounding fan cultures (and the focus of an entire special issue of the journal Transformative Works and Cultures) is the issue of entertainment professionals exploiting and profiting off of free work that fans do for them.

While people write fanfiction and draw fan art for free, producers often then try to find ways to take their work and profit off of it. In a similar vein, a fan may do the free work of petitioning to get a cancelled show renewed: the producers of that series then end up making huge profits when it is renewed while the fans who did the actual work to bring the show back are not compensated. Free fan labour is increasingly being used for marketing, merchandizing, and other work that is traditionally paid, and that generates millions of dollars in revenue for studios.

The suggestion of Collins’ second tweet is that fans should spend their time sending those involved in Supernatural ideas about how to improve their queer representation. This is, essentially, either consulting work, or the equivalent to participating in a focus group, both of which are conventionally paid positions.

The show could hire more queer writers, directors, and producers, hire equity and diversity consultants, or organize queer-related focus groups and test audiences. All of these would be direct ways to not only produce better queer content, but also to provide paid jobs to queer workers. Instead, their first response is to dip into queer fan labour as a place to have this work done for free.

Even when consulting fan labour, producers have the option to actively seek out and read existing fan responses.Supernatural fans have not been quiet about their criticisms over the years, and they have already put extensive work into articulating and expressing concerns through blog posts and social media. However, again, rather than taking the initiative to go out and consult existing fan writing, producers ask for queer fans to send comments and feedback directly to them, essentially asking them to repeat themselves and do additional labour so the producers don’t have to bother spending a few hours sifting through tumblr posts that already exist.

All of this is not to put the blame on Misha Collins himself for any of these issues: Collins has, historically, been a toric relationship to fans. He has also apologized for what he said was a defensive response based on his own naivety. I am not suggesting that Collins be held up as a particularly bad example of the exploitation of queer fan labour, particularly because his only act related to this issue is a single Twitter thread for which he later apologized. However, I am suggesting that Collins’ tweet is indicative of larger cultural trends that extend well past him, and well past Supernatural, and that they can help illustrate one of the major issues related to the relationship between producers and queer audiences.

While it is exciting to see queer fan practices acknowledged and celebrated by content producers, there is a slippery slope between producers acknowledging these practices and producers exploiting them. Queer fanfiction, fan art, and fan interpretations of shows are important cultural practices: they are not, however, an excuse for content producers to get lazy about improving their efforts to improve the representation as it explicitly happens on screen. Furthermore, if a producer is going to profit in some way off of work that somebody else did for free, there should be more effort to extend some of these profits to the person who did the work.

RELATED:

POST A COMMENT