Remembering the beloved character and his historic gay kiss…

By Steven Greenwood

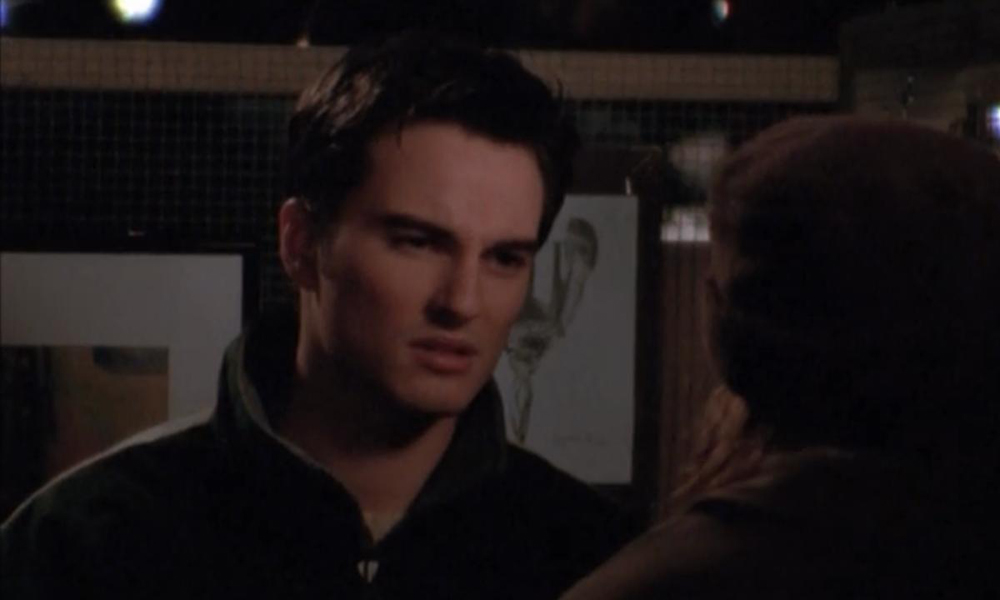

The recent release of Dawson’s Creek on Netflix Canada is conveniently timed, since 2020 marks two decades since the show’s groundbreaking kiss between gay characters Jack McPhee (Kerr Smith) and Ethan Brody (Adam Kaufman). The show’s season 3 finale, “True Love,” which aired in May 2000, saw Jack traveling to Ethan’s college in Boton to profess his love to him. Struggling to find the right words, Jack declares “I want to show you that I can, and that I’m not afraid to… oh hell… this,” before kissing Ethan.

This kiss is significant because it is often referred to as the first “passionate” kiss between men on primetime TV, and is celebrated as a major step forward for queer representation. Jack’s importance, however, extends beyond simply his kiss being a “first.” His character and storylines served as a meaningful exploration of issues and struggles faced by gay men – and queer communities more broadly – many of which are still relevant now.

Dawson’s Creek aired for six seasons – from 1998 to 2003 – and followed the lives of a group of teenage friends as they navigated high school and life in the small town of Capeside, Massachusetts. The cast originally featured four friends – Dawson (James Van Der Beek), Joey (Katie Holmes), Jen (Michelle Williams), and Pacey (Joshua Jackson) – but it added Jack and his sister Andie (Meredith Monroe) in the second season, and Audrey (Busy Phillips) in the fifth. One of the most popular – and controversial – teen shows of its time, Dawson’s Creek was known for dealing with loaded and difficult topics such as teenage death, mental health, drug use, and sexuality. Although Jack was introduced as a love interest for Joey, he comes out as gay in Episode 15 of Season 2, after which he and Joey choose to remain friends.

One of the most important features of Jack’s character is that he is not perfect. He is a flawed, complicated character who – much like the others in Dawson’s Creek – spends his five seasons on the show confronting his flaws and growing into a more well-rounded, balanced person. What makes Jack particularly valuable is the way that his flaws, struggles, and growth speak to common issues faced by young gay men. Through Jack, Dawson’s Creek provided an insightful and nuanced reflection on major issues in queer culture, particularly in the way that his story explored problems with internalized homophobia and femmephobia, as well as healthy growth and development surrounding these issues.

Shortly after Jack comes out as gay, he has a fight with Joey that foreshadows the issues that he will end up confronting through the rest of the show. In the season 2 episode “Psychic Friends,” Joey flirts with a photographer (Nick Stabile) only to find out that he is gay. She makes a passing comment about how she should have realized that he was gay because he compared her to Madonna and Marilyn Monroe. Jack gets angry at this reference, and comments that “people look at me like any minute I’m about to start tap dancing to Bette Midler albums.” Jack’s suggestion here is that there is something wrongor undesirable about people who do tap dance to Bette Midler albums, and that being mistaken for “one of those gays” is sufficient reason to get irrationally angry, as Jack feels the need to firmly cling to his identity as “not one of them.”

Despite being openly gay, Jack is terrified of being perceived as feminine or associated with femininity, as he treats feminine gay men with rejection or disdain. To anyone who has seen a “masc for masc” or “no femmes” profile on Grindr, the trend for more masculine-identified gay men to express hostility towards feminine-identified people should be a familiar issue. Jack’s behavior serves as a reflection of femmephobia and misogynist structures that are still a major issue in queer communities.

Brynn Tannehill has outlined the problems with femmephobia. Tannehill defines femmephobia as “fear or hatred of all people and things which are perceived as femme, feminine, effeminate, and/or twink, regardless of their gender,” and follows up that “passing as straight is valued, and being seen as effeminate in any way is viewed as an embarrassing stereotype.” Femmephobia is, in many ways, an extension of larger cultural misogynist norms that see anything coded as masculine as superior or more desirable to things coded as feminine.

As an all-American, football playing “boy next door,” Jack has an investment in masculine gender identity and expression. There is, of course, nothing wrong with him having a masculine gender identity and expression; however, there is a problem with the ways he uses this positioning (and his insecurities about maintaining it) as an excuse to express misogynist and femmephobic behavior towards others. He lashes out at feminine gay men as if they are something he would be embarrassed to be mistaken for and becomes more interested in defending his claim to masculinity than in defending or supporting the less-masculine queer folks he mistreats in the process.

While Jack’s discrimination against feminine gay men is a flaw with Jack as a person, it is exactly this flaw that makes him a compelling and meaningful character. Watching Jack confront and struggle with his issues serves as a cautionary tale against the dangers of femmephobia, and the internalized homophobic and misogynist drives that lead to it. His character growth, however, also offers a chance for a healthy way to process and move past these issues. In this sense, Jack functions as both a warning and a role model for gay men who may relate to his situation and find themselves falling into femmephobic thought patterns.

While the moment in “Psychic Friends” is a relatively small comment, Jack’s relationship to femmephobia develops further over the course of the show. In “Self Reliance,” Jen encourages Jack to join a local queer community group. He is extremely uncomfortable the entire time, accuses the members for having no identity outside of their sexuality (“It’s like: Hi. I’m gay. And that’s all I am”), acts condescendingly and dismissively towards the other members of the group, and eventually leaves after saying that it is “all getting a little too gay for me.”

Again, there is no issue with the fact that Jack is not as feminine or “alternative” as the other members of the group. The issue is not Jack’s masculine gender expression, which is accepted (group leader Tobey endearingly refers to him as “Captain America,” and clarifies that it is a complement) but rather that he refuses to accept or embrace the others in the group, choosing instead to reject and belittle them.

In addition to femmephobia, Jack’s behavior in this group (where he is also uncomfortable with other signs of “otherness,” including piercings and political inclinations) demonstrates an issue with to him suppressing or limiting the extent to which he is willing to talk about or express it, even as he does acknowledge it. Internalized homophobia refers to the process of internalizing the homophobic views of mainstream society and applying them to oneself (developing shame and insecurity), or projecting this shame onto others. Jack’s internalized discomfort and fear of his sexuality then manifests in a rejection of situations where he has to openly discuss or acknowledge his sexuality too explicitly, or for too long: places that get “a little too gay” for him.

Internalized homophobia and femmephobia lead to a situation where Jack is increasingly isolated from community due to his inability to accept and find solidarity with less normative queer folk. He is not willing to recognize that proximity to femininity does not compromise his own identification with masculinity, and he constantly projects his insecurities onto others. Trapped in between a normative culture that won’t accept him because of his sexuality, and a queer culture that he won’t accept because of its association with abjection and femininity, Jack ends up in a situation where – as Jen points out – his entire social circle consists of two fellow students and Jen’s grandmother (Mary Beth Peil).

The beauty of television is the fact that characters are not static, and the majority of Season 4 traces Jack’s friendship, and eventual romantic relationship with politically-active, feminine gay man Tobey (David Monahan). As Jack becomes more comfortable with Tobey’s gender expression and political queerness, he becomes less anxious about seeing queerness as a threat to his masculine identity. Jack’s relationship with Tobey breaks down the femmephobia and internalized homophobia that Jack struggles with, and he comes out of the relationship a healthier person with a better-developed relationship to the larger queer world.

Of course, character growth is never an easy ride, and Jack’s insecurities about gender come back in an ugly way in season five, when he gets wrapped up in the toxic masculinity of a fraternity at college. Dawson’s Creek, never a show to go easy on characters, does not pull punches when showing the harm that this unhealthy obsession with “fitting in” to normative, toxic masculine settings causes. Jack loses his relationship with Tobey, alienates his friends, nearly fails out of school, develops a drinking problem, and finally risks his life after jumping off a roof while drunk. It is only after he reaches rock bottom that Jack again returns to the path he followed while with Tobey in Season 4 and begins to re-develop a healthy relationship with himself, his sexuality, and his connection to a much healthier understanding of what masculinity means to him.

Jack’s ending is, ultimately, a happy one, as he ends up in a relationship with Doug Witter (Dylan Neal), who is closeted up until the series’ finale. The choice to pair Jack with Doug resolves struggles that both characters face throughout the series. While Jack is openly gay but uncomfortable with femininity, Doug is exactly the opposite: he refuses to accept his sexuality, but is open with his love of conventionally feminine and gay-coded activities such as musical theatre. The union of these two thus dramatizes a resolution of Doug’s homophobia and Jack’s femmephobia in a pairing that shows how both have, after years of development, reached a place where they can accept both themselves, and other queer people.

Dawson’s Creek today

While Jack’s history-making kiss happened 20 years ago, his journey on Dawson’s Creek is still relevant for a contemporary audience. For anyone grappling with the damaging effects of internalized homophobia, toxic masculinity, and femmephobia within the queer community, Jack’s story proves both a sobering depiction of the harms that these issues can cause, and a motivational journey of someone who is able to confront them and, ultimately, heal.

The show does not, of course, stand up entirely in a modern context: there are no prominent queer women, and all of the gay men are cisgender and white, meaning that the scope of queer characters represented in the show is extremely narrow. The show in general has an almost entirely white cast, and is to refer to Dawson’s Creek as “timeless” or perfect in its queer representation; however, Jack McPhee’s story remains impactful and meaningful for its navigation of a particular queer narrative that will likely continue to resonate with many viewers.

Steven Greenwood is a PhD candidate at McGill University, where he researches the relationship between queer communities and popular culture. His dissertation explores queer reception of musicals, focusing specifically on how this reception has changed (and the ways it hasn’t) since the turn of the 21st century. He also writes and directs for stage and screen, and serves as the artistic director of Home Theatre Productions.

Comments

1 Comment