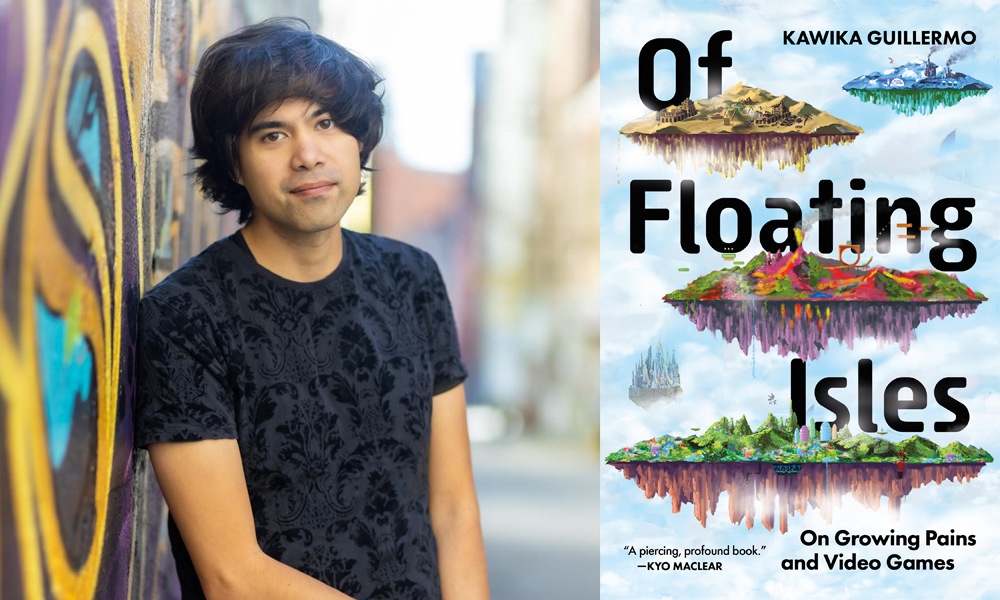

The author of Of Floating Isles talks to IN about turning games into stories of queerness, breaking stereotypes, and survival…

Vancouver’s Kawika Guillermo isn’t just a gaming expert; he’s an established author with a pretty notable career. His debut novel, Stamped: an anti-travel novel, won the 2020 Association for Asian American Studies Book Award for Creative Prose, and his second novel, All Flowers Bloom, won the 2021 Reviewers Choice Gold Award for Best General Fiction/Novel. His latest release, Of Floating Isles, is a collection of essays that use video games as a creative way to explore deeper themes of identity, belonging and community, especially for marginalized individuals.

In Of Floating Isles, the award-winning author and professor explores how video games served as both a compass and a mirror throughout his life. As a games scholar and a queer, mixed-race person, he dismantles the stereotype of gaming as a space for a single type of person, revealing it as a profound landscape for self-discovery.

IN Magazine recently sat down with Guillermo and talked about how games, far from being an escape, helped him understand his own sexuality and find solace in times of hardship. We also explored how video games can lead us to a deeper understanding of ourselves.

Why write about queerness and video games? How do they relate in your life as a gamer?

Games have been unfairly assigned this boogeyman of cis-hetero-normyness, which in my experience couldn’t be further from the truth. I mean, games are about role-playing, about hitting our unseeable pleasure-buttons, about playing with others in often impassioned, unhinged ways – screaming, jumping for joy, intensity, laughter. As soon as you boot up Street Fighter or Mortal Kombat, the first thing you do is decide what kind of gendered – or a gendered – person you want to squash your friends with. Games also give us these strange pleasure-shocks of self-recognition when we find ourselves playing dress-up, or romancing a character we didn’t think we’d be attracted to.

I think the way we have thought of games as anti-queer is something invented by big companies who want to sell games as children’s toys, and restrict their meanings for their own benefit. Of Floating Isles confronts this question I’ve wondered all my life: how can we have this daily habit involving play, interaction, pleasure and experimentation, and not see it as queer?

You return to queerness throughout the book, though the book is also about growing up very religious, as Filipino American, and facing many hardships, including the loss of loved ones. How do you see queerness formed through all these moments?

Some chapters focus on sex, gender and queerness, but you’re right that I don’t isolate queerness as one form of difference in my life. I think that’s because I’m ‘queer’ from what we see as ‘normal’ in a multitude of ways, and they are all part of being queer, too: I am neuroqueer (as neurodivergent people are often read as queer), I am Asian-queer (as Asian men in North America are particularly read as effeminate and queer), and gender-queer as well. I think for those of us who have multiple ways of diverging from the norm – and being excluded, othered – our queerness becomes invisible, as people tend to centre on other things, like our poverty, our immigration status. But for most queer people in the world – non-white, non-Western – queerness is rarely an isolated identity we get to claim. And for me, video games really spoke to that ambiguity, that mixture of otherness that we have a hard time explaining to others. Video games have always been queer, as the game scholar Bo Ruberg writes, but they have also always been meaningful as a space where participants don’t need to declare their identity at the door, or even have it all figured out.

Can you give examples of ways games helped you understand your own sexuality?

Chapter 2 of the book contains intimate moments I had with chatroom role-players, where, years before I even had my first kiss, I experimented erotically with anonymous people playing characters from the game Final Fantasy 7 – I was the pony-tailed hot mess, Reno. Later in the book, in Chapter 8, I talk about the term ‘player-sexual,’ which explains how in some games, the player can romance almost any significant character, no matter their gender or sexuality. I think of how ‘player-sexual’ can make us think differently about the cycles of being bisexual – the ‘bi-cycle’ – and how bi-erasure often comes from a fear of bisexual ambiguity, of uncertainty, which can make bisexual/pansexual people seem a threat to both straight and gay people. Yet in many modern role-playing games, bisexuality is almost a default, and it’s a given that you as a player can go any which way, that you could respond to anyone’s ‘dire warning about the yonder dragon’ with a salacious flirt. I found that this resonated with my sexuality and helped me understand my own attractions.

Much of Of Floating Isles focuses on your experience with suicidal ideation, including moments when you sought to end your own life. How did video games relate to these feelings? Would you say they rescued you in some way?

No, I try to be clear that it was people and community and acceptance that rescued me, and then knowledge, learning, love and friendship that helped me find reasons to live. Games cannot rescue us – I try to be clear about that, as I don’t want anyone to walk away from this book thinking games will save us from anything. But when we talk about these things that do rescue us – community, love, support, self-acceptance, knowledge – games are not irrelevant, either. In the fifth chapter I write about how, during a year of suicidal ideation, the game Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind helped me learn to survive by travelling and connecting with others, and by understanding myself better. And many games since Morrowind have helped me understand devastating atrocities and wars around the world, and helped me seek out the political will and solidarity to find hope in those moments – hope that is crucial to our own survival. Still, I don’t want readers to think that games could ever do all the work of saving or condemning us: that’s work only we can do for ourselves. But when we leave games out of these conversations about health, spirituality, meaning and death, we exclude so much possibility for growth and understanding, and in the end we only hurt ourselves.

Your eighth chapter focuses on the different concepts of gender formed through games, focusing on the work of trans designers and scholars. What did this work mean to you in your life experience with games?

In 2016, I started playing the game Overwatch, a game full of heroes who are diverse in just about every conceivable way: nationally diverse, neurodivergent, racially diverse, gender diverse, queer. I played Overwatch nearly every day for seven years, becoming so familiar with each of my favourite characters (almost all queer women) that my bodily habits, style and attitude began to transform. I use the concept of ‘blueprinting’ from the scholar and artist micha cárdenas to explore how games like Overwatch don’t just offer positive representation, but help us enact different ways of imagining our own desires, beliefs and habits.

One of my main Overwatch heroes, Pharah, is still, I believe, the only lesbian Arab woman in all of mainstream gaming. In a time when Arab peoples are so often depicted as anti-queer radicals, or ‘terrorists,’ Pharah’s presence really means something, not just because we see her, but because we perform her – we enact her missions, we dress her, and after many hours of playing as her we come to see ourselves through her eyes. For me, the power of video games is in these transformative moments, and I hope Of Floating Isles helps us come to terms with games, and with our messy, queer, gender-bendy selves that games help us create.

Of Floating Isles by Vancouver author Kawika Guillermo is available in select bookstores across the country now.

POST A COMMENT