Queensland and Western Australia deliver close encounters with some pretty iconic members of the native animal kingdom…

By Doug Wallace

“I’m not leavin’ til I see me a critter.”

This cartoonish line is often my opening gambit when visiting the great outdoors and it usually gets a laugh. Being a farm boy – albeit years ago – I’ve always been engrossed by animals in the wild, including the bald eagles I saw earlier this year in Manitoba, the muskrat and black bear in Nova Scotia, the whales and manta rays in Mexico, even the opossum that currently lives under the back step (whom we’ve named Roland).

My recent excursions on Australia’s east and west coasts opened up a whole new world of critterdom, with a veritable parade of pelts, scales, feathers and thick, leathery skin.

Let’s get something out of the way: most people think Australia is full of things that can kill you – sharks and spiders and snakes. And, yes, there are a number of nasty critters Down Under, but the odds of you coming across one are extremely low. You will likely never run into a bull shark or a blue-ringed octopus or an eastern brown snake. (There’s even something called the common death adder, which shows you how blasé Australians are about this.) Australia actually has fewer venomous things than Brazil or Mexico, and we don’t see you crying about that while you’re swanning around Puerto Vallarta in your G-string.

A saltwater crocodile only kills one person every three years…okay, I’ll walk it back a bit. But a funnel web spider hasn’t killed anyone in 40 years. If you happen to be a water baby, you might meet a jellyfish or two you won’t like. I remember a resort manager in northern Queensland once warning me to stay out of the ocean, because it was stinger season and some of them were “quite fatal.” As if “fatal” wasn’t enough and needed a modifier. I went swimming anyway, but I wore a stinger suit, which made me look like some sort of amphibious mime. Hell, the heat will kill you here before an animal will: it can reach up to 40ºC in parts of the outback. So seriously, when it comes to fretting about the fauna, “no worries,” like the Australians say.

A teaching moment with an endangered species

A visit to the Australia Zoo one hour north of Brisbane, on the country’s east coast, amped up the critter factor for me. The legacy project of the family of Steve Irwin (the late zookeeper, environmentalist and television personality, this 280-hectare menagerie on the Sunshine Coast is a major attraction with a wide variety of birds, mammals and reptiles. I managed to feed a kangaroo, see someone else feed a few crocodiles, and watch a bunch of very smart, very exotic birds fly around on cue.

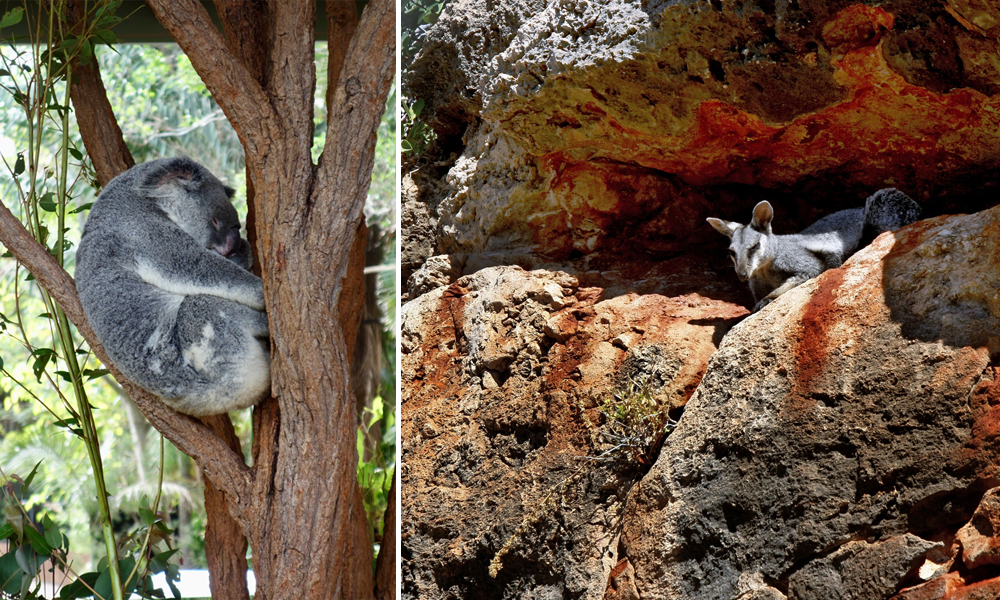

A koala bear even burped in my face – no guff! Herein lies what I’m calling the koala conundrum. In a corner of the gift shop, visitors can have their photo taken with a koala, one specifically calm enough to do so. (Interestingly, no one asked to be photographed holding the equally sleepy yellow cobra that I was glad to see safely behind a thick sheet of glass.) While the bear only “works” a few hours a week, the fact that it is being handled at all makes animal protection groups bristle. And yet (here comes the conundrum part), the Wildlife Hospital adjacent to and funded by the zoo does an amazing job of rescuing and treating drought- and fire-affected koalas, platypuses, echidnas, birds, turtles and more. There’s even a koala intensive care unit, built with a donation from Seth MacFarlane of Family Guy fame in honour of his mother. So on balance I think that perhaps my belching koala buddy pitching in for the team with a $35 photo op might not be so terrible – but I will leave that argument to the grown-ups.

In addition to the zoo and hospital, the new Crocodile Hunter Lodge adds a dash of luxury to the scenario. Little modern cabins in gorgeous surroundings a few miles from the zoo put visitors in the thick of the natural Queensland beauty, surrounded by the iconic Glass House Mountains and close to the southern Sunshine Coast beaches. This truly is a splendid part of the world.

A date with the biggest fish in the world

More critters are on my list over on the other side of the continent in Western Australia, but I am warned in advance that they may be more elusive.

I fly north from Perth to the small resort town of Exmouth on the state’s North West Cape, and one of the first things I see is an emu crossing road sign – I am certainly not in Kansas anymore. The town is a red rock-big sky kind of place, all corrugated roofs and straight, flat, dusty roads. It’s a notable jumping-off point for adventurers visiting the nearby Ningaloo Marine Park and the massive Cape Range National Park.

A hike in the 48,000-hectare Cape Range feels almost like I’ve landed on Mars, revealing a sparce, arid wilderness of rugged limestone, full of caves and nooks and crannies. Fruit bats fill what very few small trees there are, not sleeping from the noise of some of them, but definitely upside-down. The spectacular red cliffs of the picture-postcard Yardie Creek Gorge are the backdrop to our Instagram shots of the day, and as we wander along, little black-flanked rock-wallabies appear. They skip nimbly over the rocky plateau, making their way farther into the cliffside crevasses to escape the approaching heat of the day. I note later that the species is classed as endangered, and think that my critter list is not just elusive but dwindling.

A similar feeling arises the next day during a snorkelling adventure on the 260-metre-long Ningaloo Reef, Australia’s largest fringing coral reef (as opposed to a barrier reef). Within the first 15 minutes of being in the water, we spot a dugong, a member of the manatee family, and one of the rarest things to see in this part of the world. The snorkel guide is over the moon, shrill with excitement. The dugong clocks us for one, two seconds, and is gone in a flash. So glad I didn’t blink.

This “pre-show” revs us all up for the main event: swimming in the water alongside the massive whale sharks. This slow-moving, gentle fish – certainly a step up from “critter” and on to “creature” – is the largest fish in the sea.

A plane circling overhead can spot the whale sharks’ shadows, letting the various boat captains know where to head. The whole process of effectively swimming with them so that everyone has the chance to see them properly is carried out with military precision. Jumping into the water in lines of four, snorkellers pay close attention to the guide, who in turn is watching the hand signals of a spotter, who is communicating the direction the whale shark is heading. We all line up in a tight row and wait for the cue to dip our heads. And there it is – all 10 metres of it, spotted blue-gray and graceful, and so beautiful. Its mouth is huge, its little teeth straining the plankton out of its path. We maintain a three-metre distance, but that’s plenty. And when we all start to swim along, it’s not too strenuous to keep up with the three that we encounter in the span of three hours. This is a day to remember for sure.

And with that, my critter checklist – on land and at sea – is complete. And not a hairy spider in sight.

DOUG WALLACE is an international travel and lifestyle writer, photographer and custom-content authority, principal of Wallace Media and editor-publisher of TravelRight.Today. He can be found beside buffet tables, on massage tables and table-hopping around the world.

POST A COMMENT