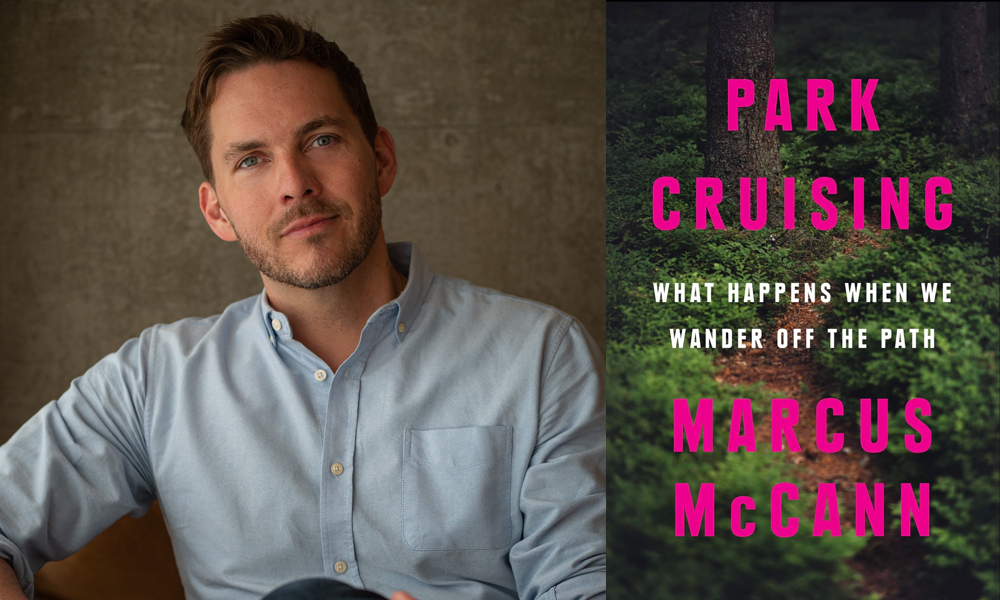

We chatted with lawyer Marcus McCann about his new book on park cruising, and how we need to consider the social good associated with it…

By Stephan Petar

Park Cruising: What Happens When We Wander Off the Path by Toronto lawyer Marcus McCann is a series of 10 essays that uses park cruising to discuss various topics such as consent, empathy, policing, violence, isolation and public space. It was inspired by his work opposing ‘Project Marie’ in 2016, which saw plainclothes police officers target men looking for sex at Marie Curtis Park in Etobicoke. More than 70 individuals were charged with trespassing and engaging in sexual activities, although charges were later withdrawn. McCann, along with other lawyers, donated his time to help the men charged.

Through the use of global studies, news reports, police records and testimony, McCann creates a compelling narrative that dismisses misconceptions, like the notion that people go park cruising out of shame, and provides new ways to think of cruising. His explanation of the legal history is digestible, presenting insightful positions on how the system should view cruising, and public sex overall.

“The general takeaway, I think, is the same for all audiences [2SLGBTQI+ or heterosexual]. As long as the law continues to see public sexuality as something that is only ever a harm or problem and doesn’t consider the social goods that can come from park cruising, then society is at a disadvantage,” McCann says.

He also hopes that even queer readers, who likely have more knowledge on the topic than the general public, will find something that leaves them saying, “I didn’t know that” or “That’s an interesting way to look at it.” That is exactly how my friends and I felt – especially around the discussions of social good and how certain factors are making park cruising more relevant.

McCann positions park cruising as a form of companionship, learning and empowerment. “What’s at the centre [of the story] is the kind of warmth that comes from the human connection: that cruising can reduce isolation and help people find and connect with each other.”

His book explores the community-building aspects, sharing testimony from those who find intimate communities among strangers. These relationships are built by having encounters with the same person over a period of time, and sometimes learning personal stories about them, all without ever fully seeing them or knowing their names. It can even be an identity-forming experience for many. “Park cruising is a site of exploration and can help people feel less alone,” he adds.

McCann gives an interesting perspective on safety, which leads to a conversation of the park design and how we negotiate the use of public spaces. “The mere presence [of people] is a protective factor,” McCann notes. This is true not only for men cruising, but other patrons not engaging in the activity. One resident near Marie Curtis Park told the group Queers Crash the Beat, who were conducting outreach in the area after ‘Project Marie,’ that park cruisers made her feel safer.

As McCann explains, parks are mixed use spaces and “everyone is safer when there are a variety of uses.” He also adds that “park infrastructure can be set up in a way that directs people to do certain things in different areas.” We can design parks in a way that is harmonious and separates activities by being thoughtful with where we place things, the paths we create and the greenery we plant.

He also has a conversation on consent and what cruisers can teach us. “In order to engage in cruising, you have to care what signals are being sent by another person. You have to be alive to the signs of desire or interest that are being shown towards you,” McCann says. He explores why this is an important aspect and challenges the traditional model of the sexual chase by repositioning and refocusing it.

Cruising has been around for hundreds of years – since 15th century Florence, Italy, according to the book. In that time, the attitudes towards public sexuality have fluctuated and the reasons we engage in cruising have changed. In fact, we’re now in a moment where economic factors have made cruising more relevant.

Affordability in relation to commercial and residential rent may be driving more people to parks. Commercial rents, and even development projects, have closed queer spaces, with barely any new ones opening.

Residentially, extremely high rents are leading to multi-person households with roommates, or individuals moving back home. “In the face of those things, where do they turn?” McCann says. “It makes sense they turn to parks.… The idea of cruising in the ’70s, where you would find someone and take them back to your modestly priced one-bedroom, is undercut when residential rents are high.”

The book is not what I expected when I first saw the cover on Twitter earlier this year. I thought it would be a linear journey looking at park cruising solely through a historical and legal lens. The more I dived into the book, the more I understood the fittingness of the subtitle, What Happens When We Wander Off the Path.

McCann creates several trails for us to walk along, giving permission to roam and choose our own route. He introduces forgotten stories, those hidden from public view, and provides information we can insert into conversation or even question. He shows us the past and the present, and provides us with a vision of how the views of park cruising could and should evolve in the future.

STEPHAN PETAR is a born and raised Torontonian, known for developing lifestyle, entertainment, travel, historical and 2SLGBTQ+ content. He enjoys wandering the streets of any destination he visits, where he’s guaranteed to discover something new or meet someone who will inspire his next story.

POST A COMMENT