If you’re looking for a good Halloween present for yourself or a loved one, look no further than Vampire Cinema: the First One Hundred Years…

By David-Elijah Nahmod

It’s hard to believe that it’s been one hundred years since the first vampire film was produced. In 1922 gay director F.W. Murnau made Nosferatu, an adaptation, or plagiarism, of Bram Stoker’s celebrated 1897 novel Dracula. That the film exists today is a miracle. Murnau felt that by changing all the character names as well as the locale of the story, he could get away with copying Stoker’s work. But Florence Stoker, the author’s widow, wasn’t having it. She filed suit, and a judge ordered every print of the film destroyed. Somehow one print survived, and because of that, the film is readily available on DVD and Blu Ray today.

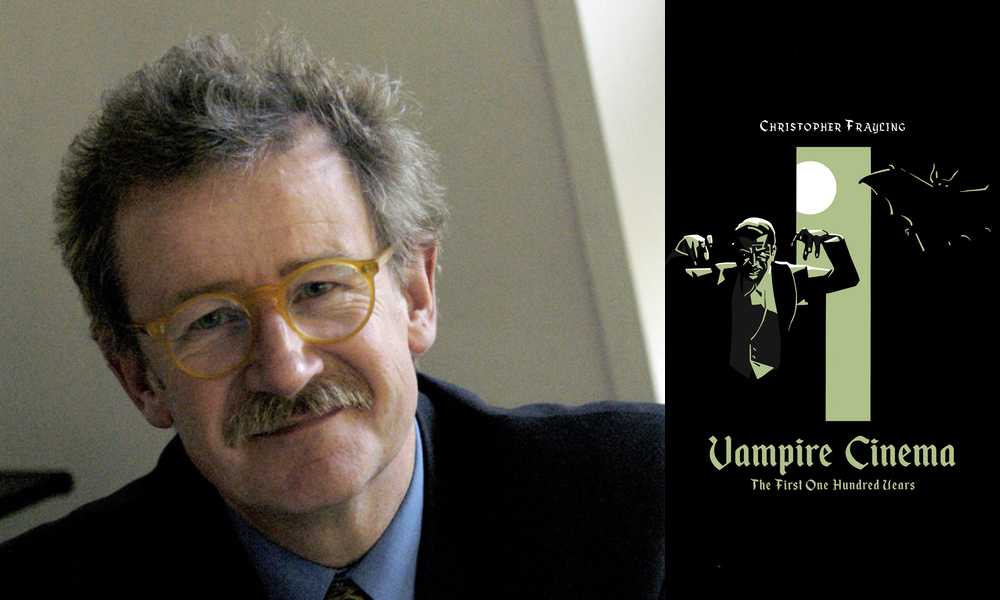

In his new book Vampire Cinema: the First One Hundred Years, author and film historian Christopher Frayling recounts this story. The book, an attractive coffee table volume with a considerable amount of text, covers a lot of ground. Frayling begins at the beginning, before movies even existed. He writes about what may have been the first vampire novel The Vampyre by the poet Lord Byron. For the next 58 pages, Frayling recounts the history of vampires in pop culture. His prose is meticulously researched. As the title suggests, the book’s main focus is movies.

For over two hundred pages, Fraylings writes about every significant vampire film ever produced, with few omissions. Each film gets a page of text, and there are many photographs. After Nosferatu, Frayling’s undead history lesson moves on to London After Midnight, now one of the cinema’s most eagerly sought after lost films. Produced in 1927, London After Midnight starred silent screen icon Lon Chaney, known as The Man of a Thousand Faces. One of those faces is on display in Frayling’s book. A photo of Chaney in full vampire regalia reveals a creature with a pasty white face, a bat-like cape and razor sharp teeth. It’s a frightening visage, and makes one hope that a print of the film will turn up some day.

Dozens of films are covered in Frayling’s book. From Nosferatu to a 2022 film called Moribus, and everything in between, Frayling offers capsule reviews and a gold mine of photographs. Most of the films covered are American or British, but there are also films from a variety of European countries, like 1960’s “Black Sunday,” a terrifying chiller from Italy which starred Barbara Steele, the first female to achieve a sustained career in horror films.

There are several titles in the book that are of interest to the LGBT reader. Dracula’s Daughter (1936), was a film which starred Gloria Holden as the screen’s first bisexual vampire, her victims are both male and female. Though he didn’t write The “L” word in his prose, Frayling does refer to the film’s “most celebrated sequence,” when the Countess seduces a young artist’s model (Nan Gray) before biting her.

Frayling does mention lesbians when he writes about The Vampire Lovers (1970), an adaptation of Sheridan Le Fanu’s novella Carmilla (1872). Frayling refers to the film as a “mix of lesbians and vampires”, as well as to Carmilla’s vampiric seduction of two girls.

But when he covers the 1971 Belgian/West German/French co production Daughters of Darkness (1971), he fails to mention that the centuries old Countess Erzebet Bathory (Delphine Seyrig) has a female companion. Frayling does hint at bisexuality when he writes of the Countess’ attempt to seduce a young couple on their honeymoon.

There’s a bit of incestuous homoeroticism in Frayling’s section on the 1971 film Twins of Evil. In that 1971 film, identical twins Mary and Madeleine Collinson play a pair of siblings, one of whom becomes a vampire. Frayling includes an eyebrow raising photograph in which one twin, with vampire fangs exposed, seduces her sister, with one hand on her sister’s breast.

Several pages are devoted to the 1994 screen adaptation of Anne Rice’s Interview With the Vampire. Frayling refers to Lestat, played by superstar Tom Cruise, as “a dashing, monstrous, bisexual vampire.” There’s a beautifully haunting photo of Cruise in full costume, and a full page image of the film’s theatrical release poster. In his text, Frayling delves into what Rice thought of Cruise’s casting, both before and after she saw the film.

The book concludes with a chapter about vampires on television. Frayling gives mention to obvious TV favorites like Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Dark Shadows, but it’s his page on the HBO series “True Blood” that would be of most interest to LGBT readers. As did the series, Frayling draws a parallel to vampires “coming out” and fighting for their rights, not unlike the fight for LGBT rights.

Overall, Frayling has done a remarkable job of documenting the history of vampires in the movies. The book is well written, insightful, and great fun to read. If you’re looking for a good Halloween present for yourself or a loved one, look no further than Vampire Cinema: the First One Hundred Years.

Happy Halloween!

POST A COMMENT